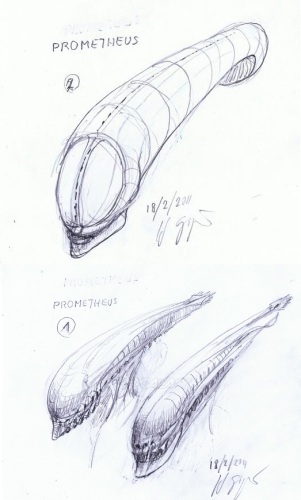

Ridley Scott had always expressed disappointment in the direction the Alien sequels chose to follow, as they never explained who the original Derelict Pilot was. ” I say we should go back to where the Alien creatures were first found and explain how they were created,” he said. “No one has ever explained why.” Originally conceived as an otherwordly creature, the so-called Space Jockey underwent a radical shift of character — transformed into a techno-organic suit.

This concept was born in Scott’s mind decades after the production of the film. “I kept staring at the skeleton which was kind of a wonderful drawing by H R Giger,” he said, “then I thought, twenty, thirty, twenty, actually twenty six years on — I thought, what if this is not a skeleton, because we only see it as a skeleton, because of our own, the way we see things in our own indoctrination; what happens if it’s another form of protection or a suit? If it’s a suit then what’s inside the suit?” He further elaborated: “I think beneath that carcass… it’s not a carcass. It’s a suit. Inside the suit is a being.”

Question of who would be the suit wearer was answered later. In 2009, it was announced that an untitled Alien prequel would be directed by Carl Rinsch, with Ridley Scott attached as a producer. In this initial phase, screenwriter Jon Spaihts was hired to craft the story of the prequel in collaboration with Scott. Assigned with the task, Spaihts immediately found that he had to solve the alleged impossibility to write a story revolving around characters that are unrelatable to. “I had the insight that if you were to try to reach back in time for the history of the universe we glimpse in the original Alien, you are inevitably concerning yourself with the affairs of non-human beings,” Spaihts claimed. “Both the deadly predator that is the through-line of the Alien franchise and the enigmatic dead alien giant that is the great mystery at the beginning of Alien.”

Spaihts’s expedient to solve the question was that whoever wore the Space Jockey suit had to have links with human history. “Those are interesting entities not fully explained, but to keep an audience interested in those things it couldn’t be abstraction, it couldn’t be a purely “alien story” about things we can’t relate to. It was going to have to be connected to our own story. Somehow the story of those creatures was going to have to be connected to the human story, not just our history but our fate to come.” Those new ideas seemingly (or deliberately) ignored the original concept where unrelatability and unknowability, as well as an utterly alien quality (which gave the original film its own title) were an integral part of both the narrative and the creatures themselves. The once otherwordly Space Jockey became the biomechanical suit of an ancient human, a member of a race labeled as the Engineers.

During the draft phase of pre-production, Twentieth Century Fox insisted to replace Rinsch with Scott — wanting to pass the project over to someone more experienced. This, combined with Scott’s own growing enthusiasm for the new direction in the story, assured him the director’s chair. Spaihts’s version of the story featured a variety of monsters — including the original Aliens themselves, and a new version of the Alien — nicknamed the ‘Ultramorph’. “I wrote five different drafts of the script,” said Spaihts, “working with Ridley very closely over about nine months. And even as we were working, we were constantly toying with the closeness of the monsters in the film to the original xenomorph. You can see an interesting balance, even looking at the movies in the Alien franchise, between homage and evolution. In every film you’ll see that the design of the Alien shifts – the shape of the carapace, the shape of the body – and some of that is to with new technology available to realise the monsters, but a lot of is just a director’s desire to do something new.”

As pre-production progressed, Scott realized that he wanted to distance himself from the original creature — thinking of it as overused. “The beast is done. Cooked,” he claimed. “I got lucky meeting Giger all those years ago. It’s very hard to repeat that. I just happen to be the one who forced it through because they said it’s obscene. They didn’t want to do it and I said, ‘I want to do it, it’s fantastic’. But after four [films], I think it wears out a little bit. There’s only so much snarling you can do. I think you’ve got to come back with something more interesting; and I think we’ve found the next step. I thought the Engineers were quite a good start.”

The same sentiment was shared by Fox, as well as Damon Lindelof, who was hired later in pre-production to rewrite the story. Lindelof’s overhaul of the script had the primary purpose of distancing it from the original Alien — thus erasing whatever appearance or notion of Aliens — either removed from the story or replaced with a different creature. “A lot of that push came from the studio very high up,” Spaihts elaborated. “They were interested in doing something original and not one more franchise film. That really came to a head at the studio – the major push to focus on the new mythology of Prometheus and dial the Aliens as far back as we could came down from the studio. So one of Damon’s major jobs when he came onboard was to replace the menaces of the xenomorphs with other things.”

Regardless, the story still hinged on the Engineers’ bioweapon — a black fluid that triggers virulent genetic and physical mutations to whatever organism is exposed to it. The new creatures of the film would be inspired by abyssal animals, parasites, and other odd wonders of nature. “Ridley is a great and ghoulish collector of horrible natural oddities,” said Spaihts, “real parasites and predators from the natural world. He had a tremendous file of photography of real, ghastly creatures from around the world – they’re chilling, some of them! He would tell these tales with relish, of wasps that would drill into the backs of beetles and plant larvae, or become mind-control creatures. Terrible things happen, especially the smaller you get. As you get into the insect world or the microbial world, savage atrocities are perpetrated by one creature on another. And Ridley was thrilled with all of them. They inspired a lot of the designs and a lot of the ideas we tried.”

One of the survivors from Spaihts’s version to the final film was the Hammerpede, a slithering creature derived from the exposure of common worms (portrayed in the film by mealworms) to the black fluid. The initial idea for the creature — as conceived by Carlos Huante — was that of a precursor of the Facehugger; the artist envisioned a creature with a centipede-like anatomy, complete with numerous gripping limbs. This derived in the creature’s name, given by the production crew, after the peculiar hammer-like shape of its head and the initial influence from centipedes.

As the design process progressed, the Hammerpede’s appearance progressively abandoned multiple arthropod-esque limbs — in favor of a smoother, limbless and more worm-like configuration. The final design was digitally realized by Martin Rezard. The Hammerpede, as it is seen in the film, was inspired by translucent abyssal animals, with evident “arteries and veins and organs sitting below the surface of the skin,” as noted by special effects supervisor Neal Scanlan.

The Hammerpede was sculpted by Waldo Mason and Martin Rezard. The design actually included several ‘layers’, ranging from the external skin to the internal organs and muscles. Each ‘layer’ was sculpted and moulded separately and then assembled onto the final model, which included mechanical features by Jim Sandys and Steve Wright. The Hammerpede’s skin was moulded in translucent silicone.

Scanlan commented: “ultimately the detail is from this beautiful sort of skeletal structure, with muscle that sits beneath, which we painted with lots of pearlescent paints and strong shades of colour. On top of that we cast a very clear skin that was very lightly textured and, in the right light, you could see through the creature and see something that was really quite interesting. One’s first impression is of something smooth and muscular, and powerful, like the body of a cobra.”

A total of 15 models of the Hammerpede were built, each with different purposes. They included a cable-controlled model with full head movement (including the opening and closure of the cobra-like ‘hood’), a puppet that could wrap around Milburn’s arm, another that could snap a prosthetic arm The puppets featured cable operated understructures, composed of several vertebrae-like segments — allowing rather fluid movements. “We used every conceivable combination to enable Ridley to do as much practically as possible,” said Scanlan. “And I also shot clean passes to allow for a few shots that could be realized in CG.”

Some shots required MPC’s digital Hammerpede — the head regeneration, for example. Shots either implemented a fully digital Hammerpede or a digital extension of the practical puppet. The CG model was sculpted by Martin Rezard in zBrush. The ‘layered’ structure of the Hammerpede was faithfully reproduced for the digital counterpart of the creature. Charles Henley, visual effects supervisor, added: “[the practical Hammerpede] had translucent skin. They had built an inside muscle layer and a second silicon layer to get a translucent look. We scanned both layers and generated a displacement map for the muscle texture. We re-built it CG with the two layer system and had all the light scattering based on the prosthetic and looking at how that was working.”

When Milburn attempts to touch the creature, the Hammerpede bites him and wraps around his arm — then breaks it. A specialized Hammerpede model was used to wrap around the actor’s arm. it was puppeteered by Ridley Scott himself off-screen. MPC also added muscular flexing as the creature constricted its coils around Milburn’s arm. The broken arm was achieved with a prosthetic mechanical arm mounted on Rafe Spall’s shoulder and another specialized Hammerpede puppet. When Fifield tries to behead the creature, its head instantly regenerates; a radio-controlled Hammerpede head and neck section was used, in combination with the computer-generated regrowing head. The creature then proceeds to violate Milburn’s mouth — a digital shot.

When the remaining Prometheus crewmembers find Milburn’s dead body, the Hammerpede springs out of it and dives back in the liquid — never to be seen again. Ridley Scott, on the set of Alien, had not told the actors — excluding John Hurt — what precisely was going to happen with the chestbursting sequence. The director used a similar trick for the scene where the Hammerpede erupts out of Milburn’s dead lips — giving Kate Dickie [Ford] only vague information. Scanlan commented: “Ridley had indicated something was going to happen. We had the Hammerpede on the end of a monofilament wire, loaded into a dummy of Milburn that was rolled over. as we pulled it out, it was clearly an enormous shock to her. The screams are real. I think she stumbles back and falls over and that’s real too.” Rafe Spall added: “I think Kate Dickie’s still having nightmares about it.”

The Fifield mutant, another survivor between drafts, was originally going to be a much more monstrous character — before being ultimately portrayed by an actor in a slightly deformed make-up. Huante initially conceived the mutation as making Fifield’s body revert back to an embryonic form — a concept called the ‘Babyhead’, whose design ancestor was an unused alien concept proposed by Huante himself for Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds.

Eventually, the design progressed into a more beastly iteration, with Fifield’s recognizable tattoo on its forehead. Weta’s digital animation referenced aggressive animals, such as big felines and gorillas. Despite the effort, it was eventually decided to excise the design from the film, replaced by a practical make-up applied on actor Sean Harris. Fifield’s mutation, as shown in the film, was dialled back to skin deformity and a bulging head.

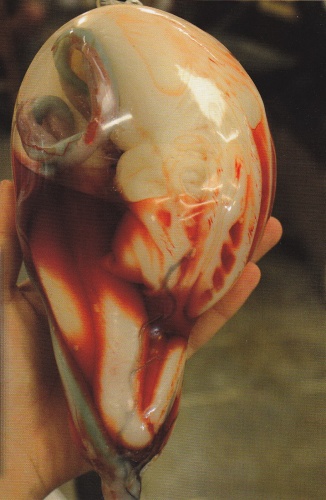

In Spaihts’ draft, Holloway was infected by a proto-Facehugger creature, and subsequently died mid-coitus when a tentacled Chestburster erupted from his body. In the new version, Holloway was deliberately infected by David with the black fluid, and his mutated seed caused Shaw to become ‘pregnant’ with the Trilobite. This new dynamic combined the Trilobite with another Chestburster, which was what Shaw originally had to surgically remove. Although it was one of the first ‘finalized’ design of the production, the baby Trilobite still went through many different incarnations before the final appearance for the creature was approved.

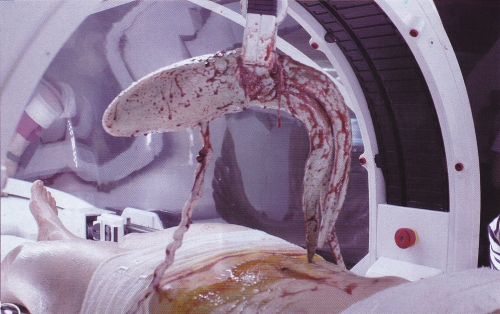

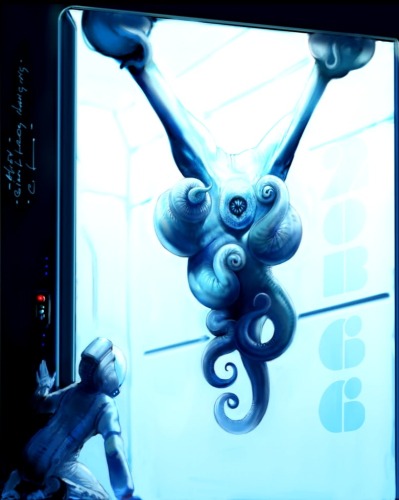

The newborn monster at first resembled a cephalopod, much like its adult counterpart. Neville Page designed the final creature — described as an embryonic form. Its tentacles are initially fused, only to progressively grow and split into more tentacles as the creature grows. Neal Scanlan Studio built a life-size animatronic, which was used when the creature is seen held by the gripper arm of the med-pod; it was sculpted by Ivan Manzella, built by Simon Williams, Andy Colquhoun and Joshua Lee, and puppeteered through a performance system designed by Matt Denton. The slithering movements of the creature were achieved with a multi-sectioned animatronic spine. The cables that controlled the creature were hidden in the gripper arm above it, so that it could be filmed at all angles with ease.

The birth sequence that first introduces the Trilobite to the screen was conceived to be particularly gruesome; Martin Hill himself was surprised by how graphic the scene was supposed to be: “When the previs came in for this, our jaws hit the floor and we couldn’t believe they wanted to go for something this graphic,” he said, “when we got on the call afterwards, ‘Really? Do you want it to be opened up this much?’ The whole sequence is very analogous to the chest-bursting sequence.”

The birth sequence was arduous to achieve. At first, Noomi Rapace simulated the creature’s movements inside her abdomen — given she had precedent experience in belly dance — with a certain level of digital enhancement. A dummy of her body, from the neck down, was created; similarly to the technique used for the chestburster sequence in Alien, Rapace sat on a chair underneat the set, so that only her head and neck would be seen. Scanlan’s team inserted the Trilobite animatronic in the dummy and maneuvered it from below, giving the further impression of the creature writhing inside Elizabeth Shaw’s body. When the creature is finally extracted, the shot features the computer generated creature, machinery and incisions. Real caesareans were used as reference for the scene. “While it’s in the placenta sack,” said Hill, “that’s fully digital. There was a model made of the placenta with the baby inside, but the internals weren’t articulated and we wanted it to convulse as it was being pulled out, which meant we had to go into a lot of scattering work with the rendering to make sure all the volumetrics worked – the blood and goo inside the placenta sack.”

The ‘adult’ stage of the creature was designed by Neville Page after a long design process that included the contribution of Carlos Huante and other artists. It is in this point of its growth that the creature effects team initially wanted to incorporate traits from an actual Trilobite — and thus labeled the character with said nickname. “One of the things I came across that I thought was appropriate,” explained Arthur Max, producer, “was a creature out of the Cambrian era you could buy a petrified version of online called a Trilobite, which is basically a very early arthropod. This particular one had feelers and a nasty kind of patina because it was petrified — and was kind of an inspiration.”

The specific Trilobite type Max referred to was Dicranurus, a genus of these ancient arthropods that sported two curved horn-like protuberances. One of the concept art pieces by Neville Page displayed the influence from these ancient creatures most evidently. The look of the creature, however, would progressively abandon the actual Trilobite-like traits and lean towards cephalopods.

Although the creature is an ‘ancestor’ of the Facehugger, the designer did not want the Trilobite to be an obvious representative of the latter creature from the Alien series. Page said: “We weren’t going to do the Facehugger, and we weren’t going to do any kind of metaphor to the first film, but at the same time this Trilobite creature became like the uber-metaphor of the Facehugger in a way, because it’s very tentacular, it’s in the same way somewhat sexual. And honestly, when I was done with the ‘face’ of it — if it even has one — it has the most vulvas that I’ve ever put into a design! [Laughs] …It was a celebration of vulvas, really, which seemed appropriate.” Earlier concept art pieces also incorporated crustacean-like traits, that ultimately did not make it to the screen-used design. The creature that appeared in the film was mainly based on cephalopods. In particular, octopi and squids in formaldehyde were thought to be interesting by Ridley Scott — due to their decayed skin, which was used as reference for the Trilobite adult’s multiple and invertebrate-like skin layers.

“There’s something about formaldehyde that turns everything pale,” explained Neal Scanlan, “It’s very insipid. So the colour is lost, and this milky white sort of creature, crammed into a jar, left a lasting impression on everybody, including Ridley.”Arthur Max added: “There was a giant squid in yellow formaldehyde in a huge glass jar which I showed Ridley photographs of, and he said, ‘that’s it, that’s the quality I want to this creature’.”

Although cephalopods were the main influence for the Trilobite, Neville Page did not intend it to directly resemble an octopus. “The fact that it had seven tentacles, that was a struggle [for] me for quite a while,” he said, “because we didn’t just want to do an octopus — and there were a few images in the very beginning where it looked just like an octopus. But in the end, it was all about one pose that I did to give it a sense of one locomotion, and make it look like there was power and strength in these tentacles to actually lift it off the ground.” The movements of the Trilobite were also based on various mollusks.

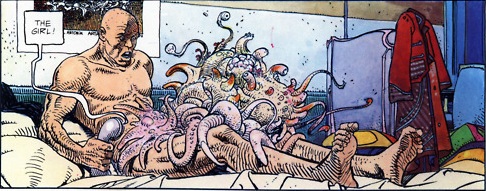

The creature designers were also influenced by artist Jean Giraud’s illustrations for a comic strip, The Long Tomorrow, written by Dan O’Bannon and published in 1975. Specifically, what served as an inspiration was an extraterrestrial shapeshifter being, an ‘Arcturian’, previously disguised as a woman, which attacks one of the characters in a sequence. The fight between the Engineer and the Trilobite is somehow analogous, although the outcome is not as bright for the pale humanoid. Scanlan commented on the design of the Trilobite: “[Page] sent a design over which you could see the origins of man in. You could see where it had come from, and you could see the prehistoric elements, and yet alien-like qualities to the character.” The special effects crew built a full-size animatronic, with complex head and mouth mechanisms, and enormous tentacles.

In the final film, the digital counterpart for the Trilobite was used for most of the sequences featuring the creature. It was animated by Mike Cozens’ team. The number of tentacles and parts that had to be animated at the same time, and the necessary synchronization with Ian Whyte’s performance made the digital Trilobite shots an arduous task. “With a tentacled creature,” said Hill, “it is always a big challenge to create an animation rig that doesn’t collapse or twist, but still gives the animator full control of where the tentacles go. Also making sure that the stretching is even across the tentacle and that one section doesn’t get stretched more than others around it, which defies the elasticity of the creature and makes it look unnatural. On top of this, where a tentacle is wrapping around the Engineer or pinned to the floor it needs to fix there, but also needs to be able to compress and deform against the surface it’s touching. Matthias Zeller, our Creature Supervisor used the layered deformer approach to the muscle rig that would fire the muscles in tension and relax them in compression. This was then passed through to a solver, which would wrinkle skin where it was more heavily compressed. Where it is stretched it would wrinkle along the tentacle. These same tension and compression attributes were passed along to the shading system so that when the skin was taught and tense it would become lighter and shinier. In compression, it would become rougher and darker in the folds of the wrinkles. On top of that there was a secondary peeling/flaking skin which sat on top of the other deformers and was fixed in place at the base of the peeling skin of the underlying structure, but didn’t stretch with the main tentacle motion.”

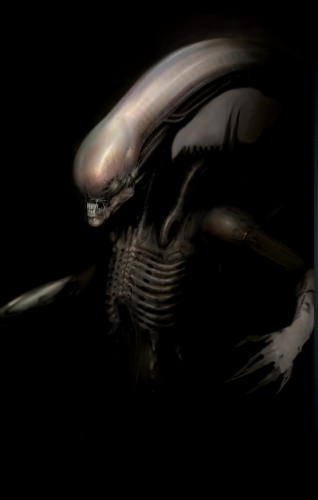

Spaihts’s original version of the story included a variety of Aliens and Alien-like creatures. Both Scott and Spaihts always wanted peculiar, new kinds of Alien to appear in the film. “[Scott] was always pushing for some way in which that Alien biology could have evolved. We tried different paths in that way. We imagined that there might be eight different variations on the xenomorphs – eight different kinds of Alien eggs you might stumble across, eight kinds of slightly different xenomorph creatures that could hatch from them. And maybe even a rapid process of evolution, still ongoing, in these Alien laboratories where these xenomorphs were developed. So Ridley and I were looking for ways to make the xenomorphs new.”

Holloway’s Chestburster grew into a pale white Alien — envisioned by Carlos Huante with a bulging Beluga-like head ending in a pointy tip. Three other Aliens, supposed to resemble Giger’s original, were also supposed to make appearances; and at the end of the film, the Engineer is killed when an Ultramorph bursts out of its chest (a remnant of the accident that exterminated the Engineers of the military installation). The Ultramorph was subsequently fought by Shaw and killed with a diamond-tipped buzzsaw. Ultimately, the Aliens were excised from the script, and the Holloway Alien and the Ultramorph (whose big final fight was also removed) were merged into the Deacon.

“The genesis of that character came after a conversation I had with Ridley,” said Huante, “about a design progression of the creatures to the xenomorph of the first film. I went home and thought about it but kept on with the Gigeresque Ultramorphs. Then as I worked I thought, ‘wouldn’t it be cool if these Aliens who are born of humans and haven’t been mixed genetically with the Engineers yet would look more human and less biomechanical’, of course this was for a different version of the script, but that’s where the Deacon (or Bishop, as he was originally named) came from. He later became an Ultramorph — and as the script changed slightly after I left the show, it became that thing at the end.”

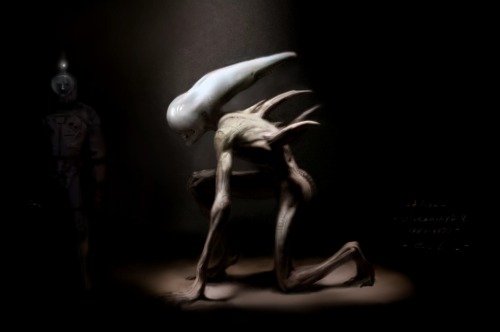

Standing about four feet tall right after its gruesome birth, the Deacon was described by the filmmakers as an ancestor of Giger’s Alien. Most of the artists involved in the creature designs for Prometheus attempted to envision the creature, with Huante leading the creative team. The creature was named after the pointy shape of the back of its head. “It looks like a bishop’s mitre,” Max said, “the evil deacon’s pointed hat.” The entirety of the concept art pieces maintained the configuration of a long head with a pointed back end. “The first impressions are often the best. I remember [that] when we joined the project there was a drawing in existence [by Neville Page] of a rather silvery metallic looking Deacon — the Deacon being the description for the pointy back of the head — still unapproved. It was quite impressionistic, but it was great,” said Neal Scanlan. The final design was the result of a long brainstorming process, which involved Neville Page, Carlos Huante, David Levy and Steve Messing — the work of whom ultimately had the most influence on the final design.

Messing’s concept art pieces were mainly based on horse foal births; the skin of the Deacon is, in fact, designed after the placenta of a horse. “Foals are gangly and ungraceful but have to grow quickly,” explained Scanlan, “a foal or a giraffe, if they’re born in the wild, out in the open, have to get on their own feet and ambulatory [sic] very quickly. They’re ungainly, but they develop fast, and that’s what we wanted, so that was the strategy with the Deacon. Steve managed to get it — something between horrific and beautiful with the way he rendered the quality of the surface treatment. It had a sort of iridescent quality we really wanted. So it was kind of beautiful-scary.” The designers also tried to infuse human elements into the creature, much in the series’ tradition. Like the original idea for the Alien, the Deacon featured feminine elements into its design — due to its ‘genetic cocktail’. “It came from Shaw and Holloway, which then produced the Trilobite,” said Neal Scanlan, “We tried to hold on to some Shaw, some femininity. It was born of a female before being born of a male.”

The Deacon’s jaw structure was based on the goblin shark, a real abyssal species with a unique ‘extendable’ jaw. This trait was originally ascribed to the Holloway Alien, and then inherited by the final Deacon. “There is a shark,” said Scanlan, “that Ridley cited as reference for us right from the start that has an entire new jaw that unfolds from the inside of its skull, so the jaw opens and a secondary jaw comes out. Had someone told me that I would have thought that was pure fantasy, but when you see the real creature, it’s amazing. Ridley also cited an angler fish that has a light that sits forward of its head, which again is an amazing thing to see.”

Huante had based his early designs on the same shark; according to the concept artist, however, they were rather different from the final result. “[the Deacon has] some of the mouth structure from the goblin shark,” he said, “or at least the concept of how the mouth shot out. The Goblin is very delicate, and my creatures were not delicate. I wanted them to be elegant but wickedly strong.” Huante later added: “I really thought they were going to make my Deacon, but for some really strange reason they went with the one from the storyboards which was not my character and not the design. The board artist illustrated it for the purposes of storytelling for the storyboards but not as the design. I had illustrated a couple of efforts for the open mouth which they showed in the documentary but they were for an even different version that was after the Deacon, when I thought of making the creature even more human. The design of the actual Deacon was abandoned.”

Ridley Scott had felt that the early takes on the creatures, including the Deacon, were “too monstrous” in appearance, and distant from reality; as such, he decided to tone them down for them to remain confined in the “realm of real”. It is noteworthy to mention that after the idea of the creature and most of its aspects were established, the concepts (among all of the other creatures’) were shown to H.R. Giger, who designed his own version of the Deacon — ultimately not considered for the film.

Once Messing’s design was selected, it was translated into a full-size sculpture, which served as the base for the Deacon puppets and for the digital model. For the creature’s gruesome birth sequence, a hollow dummy of the dead Engineer was created, and filled with internal organs and a puppet of the Deacon — which was compressed in a three-foot-diameter latex embryonic sac. The Engineer dummy was operated from beneath the set, in order for it to convulse and for the Deacon to burst out and fall on the floor. In this sequence, the Deacon was a combination of a rod puppet with digital enhancement and a completely computer-generated creature.

“We sculpted the Deacon quite late in the day,” added Scanlan, “we knew, practically, how we were going to do it, but artistically we were still unsure, so we started to sculpt a full-sized creature. It stood about four feet tall and was one of those things that once we were on the right track, the ideas started to flow in 3D. Ridley came in and we worked with him for several hours on a Saturday and Sunday and just pushed the sculpt until everybody felt, especially Ridley, that that was the way it should look. He’s very smooth, metallicy [sic]. He’s full of mercury-like material, silvers and metallics.”

Huante commented on the final Deacon’s iridescent, dark blue skin — an allegedly serendipitous addition: “Why it was blue? I don’t know… The illustration was blue so as to emphasize its whiteness in a dark blue setting and I was following some inspirational paintings that a contemporary Russian painter did of a man’s head that Arthur had sent me from Ridley. The creatures were all supposed to be albino. They were supposed to look simple, beautiful and ghostly like a Beluga whale in dark Arctic water.” Weta augmented the digital Deacon’s muscles and joints in order to make them feel more natural and realistic. Due to the creature’s unique pearlescent skin, a custom shader specifically designed for the project was used to render the way it reacts with light, combined with blood and mucus layers. The lighting was matched by Florian Schroeder and Adam King.

For more pictures of the black fluid creatures, visit the Monster Gallery.

Previous: Aliens Vs. Predator: Requiem — The Predalien

Next: Alien: Covenant [coming June 2017]

[…] Primordial Alien: the Deacon and From Beyond the Stars: Alien vs. Prometheus. […]

I really did not care for the creature design in prometheus

Tentacles?

And 8 mouths?

Thats it?

They looked impressively expensive on screen,

but the design was from every cheap Alien knock-off ever since 1979

30 years too late

Oddly enough I thought the best creature/makeup was the one everybody hated the most,

the screen used Fifield

The deacon was so poorly done that it looked like they added it to the movie at the last moment. I liked most of the other aliens and engineers in the movie, but the last one was pretty weak and too brief.

Haters gonna hate.

I, personally, liked the Deacon’s and Trilobite’s designs.

[…] Additional Data: Monster Legacy […]

[…] Previous: Aliens Vs. Predator: Requiem Next: Before StarBeast — Prometheus […]

[…] Prometheus Next: Alien: Covenant, the […]

[…] the director had said that “the beast is done. Cooked,” something that resulted in the complete excision of the Alien from the final script for Prometheus. However, the lack of actual Aliens in the prequel film […]