In adapting Gary Brandner’s 1977 seminal horror novel The Howling director Joe Dante hired John Sayles — a writer he had already collaborated with on Piranha — to completely rebuild the story, after the first drafts — written by Jack Conrad and Terence H. Winkless — proved unsatisfying. “One guy tried to adapt the book,” Dante told Combustible Celluloid, “and it really wasn’t working. That’s when I hired John Sayles. He wrote this picture after Piranha. He wrote Alligator and The Howling together at the same time in the same hotel room. You’d knock on the door, and he’d ask who it was, and you’d tell him either The Howling or Alligator and he’d slip the appropriate pages under the door.”

The new story distanced itself in certain aspects from the novel, which Dante had been dissatisfied with. In adapting the story, Dante also rejected the Studio’s proposals “to use large wolves” to portray the antagonist creatures — an approach Dante “always found disappointing” in other films of the genre. “It’s very hard to even find actors who can look natural while filming a scene with an animal,” Dante explained, “and it takes tremendous time and patience waiting for the animal to do the right thing. And that’s just for normal rabid wolves footage — nothing supernatural at all. Real wolves aren’t scary; it brings things down to nature, really robs things of any fantasy value.” The director was, in fact, adamant in the intention to portray Werewolves as beastly humanoid creatures in his film — nightmare stalkers.

A key goal of the project was to present both Werewolves and transformation from man to Werewolf in manners never seen before in a motion picture. For this task, the filmmakers initially hired Rick Baker, who at the time had been working for creature designs for An American Werewolf in London — a project that had remained to await green-light for over a decade. In 1981, Baker recalled in an interview with Fangoria: “Joe Dante and Mike Finnell called me something like a year ago. Mike had sent me the paperback novel, and they told me they were going to make a picture. Now John Landis had been talking to me about doing An American Werewolf in London for ten years. When John and I did Schlock together, he already had a screenplay. We had talked about it — there were a couple of times when it seemed it might happen, but it didn’t. Even when Shrinking Woman was cancelled, Landis said to me, ‘don’t worry, we’re still going to do American Werewolf.’ For a long time, I’ve really wanted to do a Werewolf movie; I had these ideas for a transformation scene that were going to be great, and I wanted a chance to try it. So I really had mixed feelings when Finnell and Dante said they wanted me for their Werewolf movie. We don’t have all the money in the world, they told me, but we’ll give you all the freedom in the world — and that’s very appealing to me. I spoke to Landis, and he said that we were definitely going to go ahead on American Werewolf — but I had heard that before.”

A key goal of the project was to present both Werewolves and transformation from man to Werewolf in manners never seen before in a motion picture. For this task, the filmmakers initially hired Rick Baker, who at the time had been working for creature designs for An American Werewolf in London — a project that had remained to await green-light for over a decade. In 1981, Baker recalled in an interview with Fangoria: “Joe Dante and Mike Finnell called me something like a year ago. Mike had sent me the paperback novel, and they told me they were going to make a picture. Now John Landis had been talking to me about doing An American Werewolf in London for ten years. When John and I did Schlock together, he already had a screenplay. We had talked about it — there were a couple of times when it seemed it might happen, but it didn’t. Even when Shrinking Woman was cancelled, Landis said to me, ‘don’t worry, we’re still going to do American Werewolf.’ For a long time, I’ve really wanted to do a Werewolf movie; I had these ideas for a transformation scene that were going to be great, and I wanted a chance to try it. So I really had mixed feelings when Finnell and Dante said they wanted me for their Werewolf movie. We don’t have all the money in the world, they told me, but we’ll give you all the freedom in the world — and that’s very appealing to me. I spoke to Landis, and he said that we were definitely going to go ahead on American Werewolf — but I had heard that before.”

After an unpleasant call with John Landis, Baker’s initial solution to the issue was to remain as a designer and consultant and contact his protegé — Rob Bottin — for the actual creature effects. “I really like Dante and Finnell,” Baker continues, “they are very nice people. They’d worked with Rob before, on Piranha and on Rock ‘n’ Roll High School, so I suggested that I act as designer and supervising consultant, and let Rob do the actual work. I don’t think they were as aware of Rob’s abilities as they were of mine at the time, so that made them feel better.”

A transformation test had to be devised to convince Avco films executives to provide a proper budget for the creature effects. Beforehand, Werewolf transformations had been achieved with lap dissolves connecting different stages of the transformation, represented by progressive make-up appliances. With the intention to avoid a similar, unrealistic effect, Bottin considered a number of possibilities. “We were stumped for a long time,” Bottin told Cinefantastique. “I talked to Randy Cook, Jon Berg and Phil Tippett about the possibility of using replacement animation, but that didn’t go anywhere. At that point, Rick and I were just going to do the transformations in cuts.” Miniature effects were also considered but quickly discarded.

Ultimately, the solution came through make-up master Dick Smith, who suggested Baker to use the inflatable air bladder technology he had first experimented with for the transformation sequences in Altered States. However, when Baker started design work for the Werewolves and the transformation stages, he realized that his concepts were shaping up to look too similar to what he had intended to use for An American Werewolf in London: “I modeled a head, and did some design work, sketches, and stuff,” he said, “when I realized that I was doing the same thing that I wanted to do on the Landis film; the same designs, the same process. I thought, hey, this is screwing Landis over — and screwing myself over, using all my designs on this picture. So I told Landis, Finnell and Rob that I couldn’t do any designing, that all I would do is help Rob out, give him advice, and see that things were working smoothly.” He also related in a Cinefantastique interview: “as I started sculpting, I could see it was taking on the look I wanted for American Werewolf. I told Finnell and Dante that it wouldn’t be fair to John Landis to use that design, so I couldn’t design for them, but would remain available to solve problems and answer questions.”

Bottin completed the transformation test with reviewing from Baker. “Rick had the basic idea of how he’d go about it in his mind,” Bottin said. “I didn’t know — I had only gathered bits and pieces. He said he was going to use air bladders, and other techniques, to make a mask change. I put together what I’d picked up from Rick, together with some techniques I’d used before; I described what I’d had in mind to Rick, asked him what he thought, and he said to give it a try.”

Avco, initially not intent in spending considerable amounts of money for the creature effects, approved the test. Once Bottin was at the helm of the special effects department, he was given the same range of freedom that had been promised to Baker. “When it came to the wolf scenes,” Bottin recalled, “or anything to do with special effects, Joe had told the scriptwriter, ‘look, we don’t know what this guy’s going to come up with.’ Joe figured, why write something into the script that we may not be able to do for the budget. So when the script comes to a transformation scene, it only reads ‘…and then he changed into a wolf.’ Nothing about pointy ears, the spine snapping, or the chest bursting. That was left pretty much to me, and it was great to be trusted to that extent.”

“The list of effects they wanted was amazing,” Bottin told Cinefantastique, “they wanted the most incredible transformations ever filmed. And they kept asking me, ‘are you sure you can really do all this stuff?'” The extensive body of work demanded a large crew; Bottin assembled at least 25 people for the project, including make-up artist Greg Cannom — who applied the entirety of make-ups for the film — and sculptor Dale Kuipers.

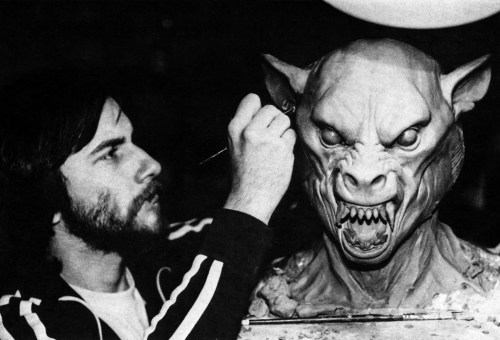

The main transformation sequence of the film takes place in Waggner’s office, when the creature starts transforming before Karen’s eyes. Bottin designed the progressive stages of transformation, starting from clay casts of Robert Picardo’s own head. “What I did was put Bob Picardo through an all-day casting session,” he said, “making 5 full-head casts — a terrible experience for him — and made all these face studies. Rather than making the wolf on Bob’s face, I made it from his face. That may sound like the same thing, but I was taking Bob’s features and distorting them, making them animalistic. I looked for characteristics in his face that could be frightening to me and exaggerated them. I think we came up with a really weird look.” He added: “I thought, well, maybe his nose would go up first, looking something like a pig’s, and then grow out from there. Then, I thought, what should the next step be? I had to guess. And I really wanted every step to be fresh. I’d do sculptures and then show them to my friends. If they reminded anyone of Island of Dr. Moreau or Planet of the Apes, I’d start over.”

The main transformation sequence of the film takes place in Waggner’s office, when the creature starts transforming before Karen’s eyes. Bottin designed the progressive stages of transformation, starting from clay casts of Robert Picardo’s own head. “What I did was put Bob Picardo through an all-day casting session,” he said, “making 5 full-head casts — a terrible experience for him — and made all these face studies. Rather than making the wolf on Bob’s face, I made it from his face. That may sound like the same thing, but I was taking Bob’s features and distorting them, making them animalistic. I looked for characteristics in his face that could be frightening to me and exaggerated them. I think we came up with a really weird look.” He added: “I thought, well, maybe his nose would go up first, looking something like a pig’s, and then grow out from there. Then, I thought, what should the next step be? I had to guess. And I really wanted every step to be fresh. I’d do sculptures and then show them to my friends. If they reminded anyone of Island of Dr. Moreau or Planet of the Apes, I’d start over.”

For the first stage of transformation, several air bladders were placed on Robert Picardo’s forehead, cheeks, neck, chest, shoulders, and arms, and concealed with make-up appliances. In addition, he also wore contact lenses and prosthetic teeth. The effect of Eddie’s nails growing into claws was achieved with a hollow insert hand with cable-controlled nails that could slowly spring out. The technique, inspired by stiletto blades, became known as the ‘stiletto nail’ effect.

Once the features on Eddie’s face begin to change more radically, the actor is replaced by a series of animatronics — labeled by Rick Baker as ‘Change-o-Heads’. The Change-o-Heads were sculpted by Bottin, and much like the test transformation head, were built with techniques first experimented on Tanya’s Island and refined for The Howling. The animatronics and their mechanical designs were devised by Bottin and Doug Beswick. Complex gear and lever assemblies shifted parts of the skull, altering its appearance in predetermined areas, such as by elongating the jaw.

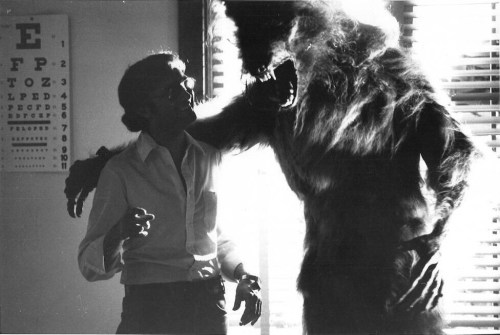

A total of three ‘Change-o-Heads’ was devised to represent the progressive stages of transformation, each capable of up to 15 different actions. The effect was also aided by editing — where each stage is shown in shots where the heads already are in motion. The transformation scene needed several takes. In one take, Picardo risked suffocation when the bladder on his neck overinflated –and generally, the bladder effects often failed to function — overinflating and exploding more than once. Certain sequences of the transformation were filmed at a higher or lower frame rate, in order to increase dramatic effect.

Other minor transformation effects in the film, used in partial metamorphosis sequences, utilized similar techniques: make-up appliances, contact lenses, prosthetic teeth, and mechanical masks. A puppet transforming hand and forearm was also devised for a scene where a severed Werewolf limb is seen. One particularly complex effect involves teeth growing into Werewolf fangs; to achieve this, Bottin built a prosthetic device hidden within the actor’s mouth. A compact lever device — concealed by a palette piece, with the tongue control in turn covered by the actor’s snarl — controlled a bar that elongated the teeth accordingly. The very structure of the prosthetic meant that it could only be shot at certain angles to achieve the desired effect.

At the end of the film, Karen White attempts to reveal the existence of the Werewolf society by transforming during filming of her news program. The single mid-transformation animatronic head devised for the sequence, a late addition to the film, was designed to reflect the fact that Karen rejected the Werewolf society, and wanted to resist her newfound instincts.

In designing the actual Werewolves for the film, Bottin wanted to avoid a configuration that would resemble other iterations of the concept seen in earlier films. “I thought to myself, if I’m going to do a Werewolf, I don’t want to do Chaney Jr.,” he related, “with a pompadour and hair on his cheeks. The Wolf Man is one of my favourite films, so there’s no reason to do that again.” The Werewolf design went through several different iterations before a viable configuration was actually chosen. Bottin continues: “I’ve never sculpted so much in my life as I did on The Howling. For the final look of the wolf I sculpted ten different heads — I wish I kept them all, but I tore most of them apart.” Several times, Bottin would reject his own sculptures for alleged similarities with designs from other films, even despite approval (and praise) from Effects line producers Steve and Jeff Shank. Ultimately, the one of the earliest versions of the Werewolf design was chosen. “We wound up using one of my earliest designs,” he said, “which I thought was horrible at first, but I wound up really liking it.”

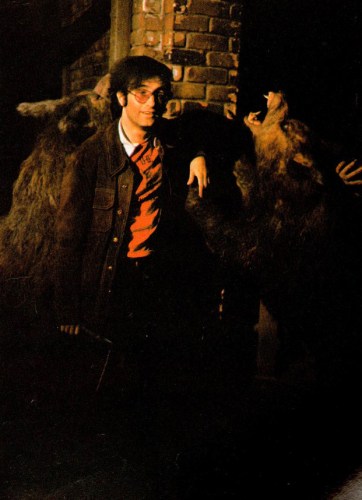

For principal photography, two full Werewolf suits were built, along with an insert animatronic head and insert arms. The results were, however, unsatisfying. “It looked like a giant chipmunk,” Bottin said. Dante was also dissatisfied — thinking that it resembled a bear, rather than a Werewolf. The initial suit is only fleetingly seen in the film, during the Werewolf attack in Quist’s cabin. Jeff Shank also devised an elaborate full-scale rod-puppet of the Werewolf, with a wide range of motion. Although successfully tested, the rod puppet was discarded and never used. Bottin explained: “there just wasn’t time to experiment with it — to work out set-ups that would hide the gizmos operating it.”

Dante demanded Avco executives to receive additional budget for the creature effects — a request that was ultimately approved. For the new Werewolf effects, Bottin collaborated with Dale Kuipers and his crew in realizing a new Werewolf suit and a hero animatronic head. Taking advantage of the extensive reshoots of the creature effects sequences, Bottin cosmetically revised the Werewolf design, making slight modifications to the configuration of the head. The structure of the snout was changed; the eyes were coloured with different hues; the teeth were altered, with shorter fangs, and a more wolf-like configuration of the incisives; the ears were elongated; and the fur on the snout and face was placed differently. The suit’s head was only capable of basic mouth opening movements, whereas the animatronic head had a wider range of articulation — with brow and lip movement. To convincingly portray the Werewolf’s digitigrade legs, Erik Jensen built insert mechanical legs, used coordinately with the suit in cuts. With the appropriate editing techniques, the nine-foot-tall Werewolf was convincingly suggested in the final film.

A deleted effect from the film involved full-size Werewolves being shot out of the barn during the climax. The so-called ‘rocket Werewolves’ were cut from the film because the results of the effect were deemed comical.

Bottin was thoroughly involved in the shooting of his effects — he directed how his work would be lit, staged, and shot. His contributions to photography granted him a credit as associate producer. “We had John Hora, a very good cinematographer, and John Murray, a very good gaffer. We all got together on the lighting of the make-up sequences, and how they’d be shot. They were so good about it, letting me get in there and make my suggestions, that I can make no complaints about the way anything was shot. Whatever is said about what’s on the screen, I’ll have to take it on my shoulders.”

The Howling, due to its limited budget, also employed replacement cel animation by Pete Kuran — for the scene where Bill Neill and Marsha Quist transform. According to Dante, the small sequence was “a partially successful experiment.”

David Allen was also hired — before the extensive creature effects reshoots — to create stop-motion sequences for the film. “Part of the reason we contracted the stop-motion,” Dante said, “was that we weren’t sure that we could get enough on the set to really suggest the appearance of a whole Werewolf.” When he began his work, Allen only had at disposal one point of reference for the Werewolf — Shank’s rod puppet — which served as a base for the stop-motion Werewolves. Allen applied some creative changes to that design. “It had a pinched waist like a greyhound,” the artist recalled, “with a full chest and almost no shoulders. That part was nice and dog-like, but I felt the legs were too thin and overly triple-jointed. I believe they built it that way so they could [move] it up in the air, making it appear to rise to a threatening height. It all seemed too precarious to me. I knew it would never look good to have models walking around on legs like that. Since they said that the legs would hardly ever show, they allowed me to change them to my own liking. In fact, they felt that they’d be using less of the rod puppet — that they wouldn’t object to any differences in my models.”

The Werewolf puppets were sculpted by Roger Dicken. Allen and Ernie Farino built the armatures, using components recycled from the Davey and Goliath TV series. A total of three long stop-motion sequences was animated. “[Allen] did three shots of the stop-motion creatures, which we were able to cut into several more shots,” Dante said. “All of them were very good, especially one very complicated shot that opened with a moving camera and ended on a static shot.”

However, after test screenings, it became apparent to Dante that the stop-motion Werewolves did not fit with the rest of the live-action footage, not only for the ‘staccato’ effect typical of the technique, but also because the Werewolves themselves looked different to the final Werewolf design used in the reshoots. “At various screenings, after the picture,” Dante recalled, “people were coming up to me and asking what picture the neat stop-motion footage came from. There was nothing wrong with those shots; it was just that the Werewolves moved differently — like in a Ray Harryhausen film where they cut from a stop-motion creature to a full-size live-action shot. Also, the colours of the Werewolves were slightly different from the full-size wolf, which we didn’t have at the time Dave Allen started up.” Only a single stop-motion shot survives the final cut — showing three Werewolves during Karen’s escape.

Despite the creative liberty on the project, Bottin was initially unsure about the quality of his special effects. However, Dick Smith — who had suggested the use of air bladders — praised the results of the then young artist’s work. “When we cut it together and looked at it,” he recalled, “I was not impressed. I was so close to it, I knew how everything worked, and I didn’t know what to think. It looked kind of neat, but I just didn’t know. Then Dick Smith was in town. I’d met with him before, on The Fury but I was really just a kid at the time. So he called and said he wanted to meet me, and that he’d heard from Rick that I was doing some interesting work on The Howling. It was really a thrill — ‘Dick Smith wants to see my work!’ — but I was a little afraid he might get mad when he saw it so I said, ‘Dick… I used some of your tricks on The Howling.’ There was this pause on the line — and he said, ‘well, I certainly hope so!’ I took him down the editing room, we ran it for him and he said it was very good. That’s when I knew it worked. I really didn’t know whether I could be proud of it until that minute. Now I’m overjoyed about the way it came out; but I’ve learned so much, and in seeing The Howling footage, I’m really excited about what I’m capable of doing now. I’ve learned so much in doing it, that I really wish I could do it again.”

Rick Baker also praised Bottin’s groundbreaking results. “It’s pretty incredible. He did a great job and I’m really proud of him. I’ll have a hard time [with American Werewolf] competing with what Rob has done — it’s almost like I’ve created a Frankenstein!”

Rob Bottin ultimately commented on the experience — his real first major effects project: “this was, for me, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to put some of my best ideas on the screen. It was painstaking, difficult, often back-breaking work, but I loved every single second of it. Besides Werewolves are my very, very favourite creatures.”

For more images of the Werewolves, visit the Monster Gallery.

LOVE everything about this! Joe Dante is one of my favorite director/producers namely for his cartoon-esq characters sometimes in his films like the episode “It’s a good life” of Twilight Zone: The Movie which I absolutely love.

A good read

Neat note about Karen’s cutesy transformation being a deliberate in-character effort to restrain the Beast. Thanks for sharing such in-depth material.

Thank you for the kind words!

Heyo, love your blog! But could you name the various sources for the quotes and information? I’m writing up on this film (as well as American Werewolf in London) and would love to know the sources of these quotes, theyre more detailed than the ones in the bluray behind the scenes!