Alien³ was a troubled production from beginning to end, and the creature effects department was no exception: the artists were plagued by constant changes in direction and contradicting studio decisions. Gillis recalled in an interview with Fangoria: “Fox never had a problem with coming back and saying ‘sorry guys. We know you built these things, but there’s a new direction, and we’re not going to use them’. We had to keep ourselves and the crew orally afloat, because people put their blood, sweat and tears into the stuff, and have a tendency to get upset when an effect’s cancelled. There were six stages of Aliens, count them! But we’re not griping about the script changes, because any story should constantly be honed. That only shows us the film’s getting better, and if the effect doesn’t serve the plot, then there’s no reason for it.”

Even though Giger’s Alien designs for the third film were not used as he conceived them, some of their characteristics made their way into the final creatures devised by Amalgamated Dynamics. First to appear in the film is an Egg, placed ambiguously in the Sulaco — built as a static model, as the only sequence showing it was a very late addition to the film.

Initially, the shooting script for the film introduced a particular Facehugger which would carry an embryo of an Alien Queen inside — the aptly named Super Facehugger. Its special purpose was visually reflected by its design. Gillis explained in a featurette: “we designed it so that it would reflect the armour-plated, exoskeletal quality of the Queen, but transferring that onto the Facehugger body design.” The armoured creature was also given webbing between its limbs, probably inspired by Giger’s aquatic Facehugger designs. The Monster, sculpted by Gary Pollard, was cast in urethane — with an understructure that simulated bones and was positionable. The Super Facehugger was cut from the theatrical version of Alien³, and was only reintegrated in the 2003 Assembly cut.

ADI also constructed a more traditional Facehugger as an animatronic. “We used the same design as the original Facehugger,” Woodruff told Cinefex, “but we had to splay it open a little bit because this one had much more movement in the front fingers and we needed extra room for the various mechanisms. We also sculpted new finger skins because the fingers were a little bit longer.” In the original version, the Facehugger impregnates one of the oxen used to drag the crashed EEV ashore. The animal dies, but the Alien inside it does not — and bursts through its corpse.

The design of the infant Alien implemented anatomical structures of a quadruped and was strongly influenced by Giger’s earlier attempt at designing this stage of the creature. The ‘Bambi-Burster’, as it was affectionately called by the crew, was gangly and foal-like in proportions. For the bursting sequence, a dummy of the ox was built by Alex Harwood and Monique Brown, and filled with false guts and blood. A simple foam form of the Chestburster was mounted on the end of a ram rod and was pushed through the carcass model (which had been fitted with a hole on its back). Several takes were filmed, but Fincher found none satisfying.

The director decided to change the scene completely and selected a new host inside which the Alien would gestate: a Rottweiler (named Spike in the film). “I wanted something faster and more predatory than an ox,” Fincher said. “As a result, the final Alien is not as elegant a creature as it was before, but it is more vicious. The change to a dog broke everybody’s heart — because it had been done before in The Thing — but it helped when we got into the big chase sequence at the end, because it gave us exciting POVs and explained the ravenous attack mode that the thing was in.” The choice was controversial, and Fox officials refused to allow the scene to be shot. Early test screenings of the film did not portray the Chestburster scene at all. Fincher recalled: “we previewed it to audiences, and people would ask, ‘where did the Alien come from?’ So I said to Fox, ‘can I shoot the fucking dog now?'” The scene was ultimately shot in the span of two days, with an animatronic Chestburster bursting through the dog puppet.

Fincher initially wanted a dog to perform as the Chestburster scuttling away from its birth side. Alec Gillis recalled: “we looked at a bunch of lanky dogs and chose a whippet. I made a little suit for the dog to wear, just using foam skins for the Bambi-Burster that I snipped and tucked and placed over a spandex leotard. She was really a great little dog, but Fincher decided that it wasn’t working because she ran in a very straight-legged fashion whereas we wanted more spiderlike movement. I think it could have worked in a quicker cut, but what he needed was a shot of it running all the way down a hallway and around a corner. We just pushed the idea a little further than it could be pushed.” The idea imposed several practical limitations: the dog “wasn’t too thrilled about wearing the head,” according to Gillis, and thus had to be dressed with a helmet that could not cover the front of its head — something that limited the possible camera angles. Richard Hedlund, visual effects producer, asserted that the final shot “was so silly looking [that] in the dailies you were on the floor, laughing.” The idea was obviously discarded, and the final scene employed a fully articulated rod puppet and point of view shots.

The Alien is next seen when it is discovered by one of the prison mates — Murphy — whom first finds the Alien’s molted skin. Murphy inspects a hole, only for the Alien to attack him with an acid spit. The sequence employed an ‘adolescent’ Alien hand and rod puppet, sculpted by Jose Fernandez. “The head was 16 to 18 inches long,” Woodruff said, “I puppeteered it for the shot, pointing it at the camera and using a video monitor to aim it right at the lens. As it comes into the light, it spits the acid out of its mouth. We had a hose inside, attached to a lever, so that we could shoot a spurt of this greenish-yellow spit.” In other scenes, effects of the Alien’s blood were achieved with caustic soda poured over sheet aluminium.

The adult Alien was the main concern for the special effects crew. In contrast with the precedent chapters of the series, Fincher intended the Alien to be seen more clearly. He explained: “philosophically, we went into the Alien effects in a different way. I didn’t want them to be ‘framed’ effects shots, with everything else just clearing out of the way. To me, the Alien wasn’t just a Monster, it was a character. So we decided that we were going to see the whole thing this time, as much as possible. We wanted the creature to walk on the ceilings and really sell the idea that this thing is a bug from outer space.”

David Fincher famously summarized the creature in Alien³ as “a freight train crossed with a jaguar”. In the film, Golic calls it “a dragon,” and in the extended assembly cut it is implied he worships the monster. Early on, the director discarded the possibility of a fully animatronic character, instead choosing a creature suit to portray the Alien as was done in the earlier productions. In addition, to properly depict both the Monster’s inhuman geometry and its agile, predatory movements, the suit was to be combined with a small scale puppet — the construction and animation of which was assigned to Boss Film Studios.

Expectedly, considerable time was spent in designing the adult Alien. “We felt that we should take the Alien in a different direction,” said Gillis. “The idea was that the creature would be constantly mutating to adapt to whatever the environment was, which gave us reason to have an Alien that was considerably different from the Alien Warrior in any of the other films. But, ultimately, Fincher decided that he wanted to remain basically with what we’d seen in the first film.” Bringing forth a concept that dates back to the pre-production of the original film, the Alien would take genetic traits from the host it gestated in. “We wound up with an Alien that was more of a quadruped,” Gillis said, “and could run very fast on all fours, while still being able to stand up on two legs.” One of the innovations was, in fact, the digitigrade structure of the Alien’s legs, a trait taken from its host. Though Giger’s designs for Alien³ were not actually used, they were used as references for many aspects of the final creature: most importantly, the new Alien sports fuller lips, inspired by Michelle Pfeiffer’s — although less prominent than Giger’s version. “Fincher wanted more of a lip structure than had been seen before,” Gillis said, “so this Alien had more human-looking lips over the top of its teeth.” The signature pipes on the back of the Alien were also removed, always in line with Giger’s innovations: this was a reason of concern, and the director went back and forth between actually incorporating them into the creature and omitting them; ultimately, he settled on an Alien without the pipes on its back. Also influenced by Giger’s designs was the return of the signature translucent dome of the first Alien, even considering its impracticality on set. “We always felt it would be worth the extra trouble,” Gillis said. The structure inside the dome was redesigned, with partially overlapping ridges. Also returning from the original design was the additional opposable thumb on each hand. In addition, partially in line with Giger’s designs, the new Alien was given a more prominent barb on the tip of its tail, although not as large as in Giger’s version. The final design portrayed by the rod puppet was also altered before filming.

ADI based the textures of the Alien on Giger’s own Necronom paintings, and possibly his designs for Poltergeist 2 [for an in-depth visual comparison, visit Alien Explorations’ article]. Woodruff told Strange Shapes and Monster Legacy: “During the build on Aliens, Fox provided us with many pieces of the original Alien creature suit and head. Within those pieces, you could actually see castings of mechanical bits; valves and plumbing pieces, some with catalogue numbers visible that had been etched into the pieces that were molded. On Aliens, those pieces of the new suits evolved to be more organic and not just castings of off-the-shelf hardware. But the suits were still very broad in that they were sections glued to a spandex leotard with nothing more than slime-covered spandex to span the space between built-up sections. On Alien 3, we took that to the next step and sculpted an entire body suit – not in an effort to make it look different – but to make it look more complete since the shooting style was going to be completely different and lighting would be revealing more of our single Alien than the hordes of the Cameron film. We relied heavily on images of Giger’s work from his own Necronomicon as the guide, seeking to replicate the organic life of that creature in more specific ‘Giger’ detail than what was represented in the work of both Alien and Aliens.”

Woodruff also said: “it was a whole sculpted suit made out of spandex and foam rubber, and we were really pushing it to the limit. We did a bodycast of me, shaved it down and sculpted over it so that the suit would have to stretch for me even to get into it. It was absolutely skintight to keep from wrinkling and buckling in strange ways. We had an amazingly fast and effective English sculptor named Chris Halls who did a large percentage of our sculpting, including the Alien head and some of the suit.”

A total of six suits was built, with one of them adapted to a stuntman. The inhuman hands were engineered with mechanisms that allowed the additional thumbs to move when the performer moved his own. The suits could also be fitted with leg extensions, which would never eventually be shown in the film. “They were fiberglass shells with struts and springs for the toes,” Gillis said. “We ended up not using them because they bulked up the legs a bit, and also because Tom would have needed a smooth runway to maneuver on and most of the sets were pretty cluttered.” Generally speaking, the suit was intended to be shot “no wider than the waist up,” according to Gillis. “Otherwise you would start seeing more of the waist and the legs, which were not quite as thin or dog-legged as the puppet. But we got all the detail a costume can provide.”

The suits could be equipped with an animatronic head. Its full facial articulation allowed both sides of the lips to move independently. It also featured tubes pumping methyl-cellulose to simulate emission of saliva. An insert animatronic head, dubbed the ‘attack head’, was also built. It was engineered with a projecting tongue driven by a pneumatic piston, devised by Paul Dunn. By pressing a trigger, the air piston would be released and the tongue would be would be violently ejected outwards. This head was used, for example, in the sequence of Clemens’ death — where the character was portrayed by a fake head built in fiberglass, filled with animal blood and entrails, and covered in wax. The head contained an air hose. “When the Alien’s tongue punched it, we fired the switch on the air hose,” Gillis explained, “and blew the brains out. It was pretty effective, as well as gruesome.”

A total of three versions of the Alien’s tail was built. The first tail was a cable-controlled tail that was not attached to the suit, but rather lined up to it — always filmed with the lower body area of the Alien cut out of the frame. Another tail was a self-supporting tail, attached to a rig that adhered to the performer’s waist and a series of supports on his back and chest. “That was supported with a sheet of plastic inside so that it could stand up,” Gillis said, “and Tom would be able to thrash it around from side to side.” The third tail was a stunt tail, attached to the suit through a similar, but simpler belt-type rig, and maneuverable with wires.

Filming the scenes scheduled with the monster suit proved to be difficult for Fincher. “It was beautifully sculpted,” the director said, “and really well put together, but it was still very difficult to hide the human form inside. The suit gave itself away with certain movements. One of the brilliant things that Giger put in the design was the hammerhead– which helps to draw you to the face and not concentrate on much else. Still, there was only so much of just head and shoulders we could show before people would start to say, ‘you’re putting me on.'” Woodruff performed as the Alien creature all the required scenes of the live-action schedule, save for one. Those included both sequences for the film itself and reference footage for the rod puppet animators. The suit did not house eyeholes, and the actor was completely blind; he was directed by other crewmembers through a walkie-talkie headset.

Woodruff’s endurance proved to be useful not only for the length of the shooting schedules, but also for the suits themselves. Gillis said: “Tom is the best performer in suits that I know. Not only does he have amazing stamina for enduring the things; but by building them he knows what their limitations are. He knows how to move to get the best look out of them. When you have an actor in the suit, you have to have zippers and things in the appropriate areas for them to relieve themselves. Tom simply doesn’t eat or drink when he’s in the suit. He’ll wear it for 13 hours at a time without having to go to the bathroom. As a result, we can make the suits more form-fitting and seamless. Tom also had a vested interest in making the suit work; so if he has a complaint about something, he’ll quietly come to me rather than shout it out to the production manager. Generally, I work with the director and then coordinate with Tom. Sometimes Fincher would say things like, ‘tell Tom not to make it look so much like a Barbie doll,’ or, ‘tell him to up the scare factor 20 percent,’ and I’d tell Tom what I thought he meant. Fincher was great. He had done stop-motion, so he’d been around Monsters and knew aesthetics and dynamics.”

Instructions and directions given by Fincher were quite extensive as well, as recalled by Sigourney Weaver herself. “One time I went around the corner [of the set] and I heard Fincher talking to Tommy,” the actress said. “He would talk directly into [Tom’s] earpiece. He was saying, ‘you hate that bald bitch, you hate that bald bitch! Get her, get her! There’s that torch again! You hate that torch even more than her! Get her!’ It was like he was whipping Tom into this lather of hatred. It was wonderful.”

Fincher wanted the Alien in his film to have an inhuman geometry and to perform complex, agile movements, obviously impossible to achieve with a creature suit alone. To properly portray the Monster he wanted, it was decided to combine the suit with a miniature rod puppet. Gillis and Woodruff designed the rod puppet, which was sculpted by Chris Cunningham and built at Boss Film Studios. “We’ve done miniature puppets before,” Gillis recalled, “And we felt that it was important for continuity that we make the puppet — but that was impractical since we were stuck in England, so we did the next best thing. Since we had access to the director for approval, we finalized the design, Chris Halls [Cunningham] sculpted it, we ran a mold and then we sent it to Boss with a painted model as reference. From that point on, it became their deal.”

Although Fincher had approved ADI’s design, the creature needed structural alterations to erase foreshortening issues in miniature photography and for other practical reasons. Lead puppeteer Laine Liska explained: “we made a lot of changes after Fincher saw it on film and saw it moving; the original design had a tendency to look a little stubby when seen from the front scuttling on all fours.” Five additional vertebrae were implemented into the thorax of the Alien, thus erasing the foreshortening issue. The digitigrade legs were also shortened to enable them to move more naturally than before. Final tweaks included shortening both the arms and the tail. The final Alien rod puppets were 40 inches long and 18 inches tall and were fitted with an extendible tongue that, however, was never actually used during filming. Their skin was cast in foam latex, with the dome portrayed by translucent vacuformed plastic.

The internal armature of the puppet was conceived to be simple and easily maneuverable. Liska explained: “for a lot of the joints, like the elbows and wrists, we used bicycle chain because it is a good, strong joint with a fixed direction. Places like shoulders and hips were left loose so they could move in all directions. Electing not to do too much internal cabling gave us much more freedom because we didn’t have to fight cables which might not hold the weight or might sometimes fight the rubber skins.” The armature and its mechanisms were devised by Craig Talmy.

Animating the puppet and compositing it convincingly within the film posed several different issues. Fincher wanted the movements of the Alien to be distinctly and unmistakably inhuman; the Horror had to move quickly, darting through corridors. A lethal predator. In addition, Fincher’s filming style included frequent camera motion, further complicating the process. Boss Film Studio first developed a motion control field recorder able to record fast tracking camera motion (such as panning, tilting, or booming). Richard Edlund explained: “we would have to scale the motion control camera system’s dynamic directional moves and scale its nodal point position to match the miniature. The moves could be preprogrammed or altered if we chose. It had to be a quiet system and it had to be repeatable within a few thousandths of an inch over a long dolly track. We had a lot of requirements which aren’t normally met by this kind of equipment. We stuck our necks out and invested our own money to build it.” Boss Film’s motion control system was designed and supervised by Phil Crescenzo, and engineered by Steve Kosakura. The software that controlled it was instead devised by Kuper Controls. It used a Fisher 9 dolly retrofitted with servo motors and electronic components and had to be as silent as possible. It was used to shoot clean plates and the Alien puppet, with the right adjustments and modifications applied.

The original plate sequences shot in Pinewood were in either 24fps or 30 fps format; the field recorder had to be designed to compensate for the different film rates. Once the background plates were recorded, the actual filming of the puppet began. Fincher wanted the puppet to be shot on an even higher frame rate than the background plates; for this reason, Bill Thomas applied further modifications to the software that ultimately allowed the puppet to be shot at any frame rate up to 60fps. “All we had to do was punch in a number,” Crescenzo said, “and the motion control system would play back the recorded move at whatever scale speed we needed to match the frame rate.”

Though the go-motion technique had been successfully used by Industrial Light & Magic on other films — such as Dragonslayer and Willow — the special effects crew quickly discarded the idea and thus began elaborating a different approach. “Go-motion has hideous complications,” Edlund explained. “With 50 channels of motion control, slow and lugubrious work and extensive programming time, everything is very difficult and lacks flourish. Rather than go that route, Fincher wanted something more flexible — which, in the course of its development, became a high-tech rod puppet technique. Using that, our takes could range from one to 48 frames a second and encompass prerecorded camera moves. We could also motion control just a few puppet channels if we needed speed or the moving of large mass. With all these possible variables, it became a limitless type of system.” Liska doubted that the new approach could be used entirely successfully. “I was probably the hardest one to convince,” he said, “because of my stop-motion background. Richard was pretty insistent on the Alien being a rod puppet, and the director seemed adamant that it not be stop-motion. But he also wanted to make sure that it didn’t look like a man in a suit. if it had been up to him, it would have been a fully articulated robot — and we’d still be making it.” The new combination of techniques was labeled by the crew as mo-motion.

The Alien was puppeteered by a multitude of crewmen moving its various parts with rods or wires, which were painted to match the colour of the Monster in order not to be detected after compositing. Each rod was equipped with a block with handles on the receiving end. Up to six puppeteers maneuvered the puppet. Most of the times, Liska puppeteered the head of the Alien, with other puppeteers moving the components of the body. Craig Talmy, Douglas Miller, William Hedge, John Warren and Brett White all contributed to the animation of the Monster. “There was something really interesting,” Fincher commented, “a more animal feeling, about bringing five intelligences to bear on a single puppet. It gave it a sort of an insect quality, like the way a tarantula [sic] walks around without any sort of order to its feet.” Various parts of the creature could be connected with the puppeteering rods: the sides of the head, the ribcage (in three different places), the hip (near the base of the tail), the hands, and the feet. Wands or wires were alternately attached to the tail to move it. The number and attachment of the rods were obviously dictated by the specific sequence and frame that had to be shot, as well as the relative position of the Alien in regards to the camera.

The trunk of the puppet was connected to a motion-control mover to enable the gross motion and to maintain the creature in the proper place of the frame. During filming of certain scenes, however, the mover proved to be an obstacle to the actual animation. Liska recalled: “the Alien tended to move like a bunny rabbit, and we couldn’t seem to get past that because the computer kept smoothing things out. David was going for movements that might resemble something familiar, but not anything in particular. We were first told to make it run like a cougar. We looked at cougar footage: and when we did our original tests, we pretty much got that. But that ended up not being what he wanted. Other characters were suggested, like a spider or something else that was gangly. David was going for the oddest configuration that we could get. We found that rods and manpower helped it to look as erratic as possible.” The Alien puppet was shot against a bluescreen and was put elevated from a reference flat surface, in order to minimize the rotoscoping work.

For each single shot of the Alien, the average number of takes floated from 20 up to 100. Scenes including the Alien darting on the ceiling had to be actually shot with the puppet upside down, because the motion control system could not flip the motion files. One of the main concerns, obviously, was actual environment interaction. The crewmembers first experimented with various kinds of plexiglass — from clear plexiglass to blue plexiglass — to provide reaction of the Alien to surfaces. Although some of the experimentation was successful, the small nuances were hardly noticeable on film.

Another major issue was represented by lighting. The puppet had to be intensely lit in order to portray proper depth of field; the consequent heat on the stage was uncomfortable to the crewmembers — and even to the puppet itself: the thin, vacuformed plastic used for the dome was frequently subject to cracks due to the heat, and thus had to be constantly replaced. In addition, the puppet frequently moved beyond the edges of the blue screen by accident — a problem solved with a new, smaller screen that was rigged to move along with the puppet. Though extremely complex to achieve, the miniature photography process was successful — also thanks to an innovative system that allowed the Boss film crew to preview composites on stage: it allowed a certain shot against the bluescreen to be recorded and electronically composited with the plate, already converted to video format, on laserdisc. The system was designed by Phil Crescenzo. “The laserdisc video comp gave us the ability to tell whether the creature was interacting with the actors or bumping into things,” said Edlund. “We had to know right away because we didn’t have the luxury of shooting the scene and leaving the set-up until after dailies. There were a lot of shots to do and we had to be able to move on with impunity, knowing we had the take.”

In order to reproduce on the Alien sudden lighting effects such as those caused by torches, a specific code, called ‘flicker processing’, was written. “[It] allowed us to follow a particular area in the plate,” Crescenzo said, “and create a table of its relative intensity per frame. Steve Kosakura then put that data into the motion control system to run light gags and replicate the flicker and whatever else directly on the puppet. Doug Calli operated the laserdisc system and contributed a lot of input to make things happen more quickly.” Rick Fichter added: “without the laserdisc system, you would have to make your best guess at a take and then weed through them later. The tendency might be for a director to overshoot in order to make sure that he got it right. The laserdisc allowed us to zero in on a specific action and a specific take without having to go through the usual black-and-white tests, wait for the dailies and then go to optical before we could see the results. We could tell quickly whether or not everything was locked into the plate. We also used the system for elemental shooting wherever we needed a quick turnaround — for steam and smoke and fire elements, mostly. It really sped up the whole editorial process.”

The laserdisc compositing gave the crew data in a far shorter time than it usually would have taken. “There were certain things I wanted in the movement that we never nailed perfectly,” Fincher commented, “and in some ways, mo-motion hindered what I wanted. But in other ways, we got fluky things that looked cooler than anything we could have imagined. We found that if we got the head and tail right, then it didn’t really matter what the legs were doing. The tail was what made it look organic and the head was what made it look like the Alien. When those two things were in synch, that was usually when we had a take that we liked.”

Once a certain shot was deemed satisfying, the components had to be actually composited together and finalized for the film. Fincher wanted a darting creature that would thus produce a blurring motion; he suggested using an additional optical shake to the scenes involving the running Alien to highlight the sense of frenzy in those sequences. In post-production, the director also asked for other modifications. Optical chief Michael Sweeney recalled: “[Fincher] wanted to change the size on some [sequences], add elements to certain shots, drop other shots, put shots on hold that they had brought back and reinsert sequences that had been deleted. You always want to look at a scene if it’s simply the Alien over a background, for example, but that’s just where it starts. Just shooting the Alien against a bluescreen involves a number of colour separations and cover mattes. We also added in shadows, debris, smoke, fire and animation lights. I would guess the most we had to deal with in any one shot was 22 to 25 elements.”

Boss film Studio’s computer graphics department also largely collaborated on finalizing the sequences. Most importantly, the Alien’s shadows were mostly digital additions to the shots, which would have otherwise needed extensive rotoscoping work. Digital effects supervisor Jim Rygiel explained: “the bluescreen puppet element and the background plate and scanned them into the system; then, by making a matte of the bluescreen element, we were able to create the shadow simply by bending the matte over as the light source would suggest for a shadow. By using the background, we were able to distort the shadow, bending it to actually fit over pipes and along walls, whatever. So the shadow would sync up one-to-one with whatever the Alien was doing.” Due to the extensive motion blur, the mattes were also digitally enhanced.

The Alien is ultimately trapped inside the refinery and seemingly killed when Morse pours the molten lead on it. However, the Monster erupts from the pool of lead, only to be quickly dispatched with water — which cools the lead. The sudden temperature differential causes the final explosion of the Monster, dispatched once and for all. For this particular sequence, lead-covered versions of both the suit and rod puppet were constructed. The Alien jumping from the molten lead was actually filmed on stage. Crewmember Al di Sarro said: “ADI made us a fiberglass mould of the body and we skinned it with the Alien suit. We made a special air mortar to accommodate the body and incorporated that mechanism into the mould. On cue, we blew that Alien through about five feet of the lead mixture at 260 pounds of pressure. It flew 15 feet in the air and threw lead everywhere. To make the Alien look like it was smoking from the molten metal, we used a cigarette smoker, purging a lot of tobacco under pressure to create a cool smoke coming out of the suit.” Once out of the lead, the Alien moves about frantically. For Woodruff, it was one of the most difficult stunts. He recalled: “climbing up pipes while covered with that slimy stuff was almost impossible. We had one set with pipes running horizontally on the stage floor, and at the back end of those was a pit for the top of the lead mold with the lead fluid in it. Fincher mounted a mirror at 45 degrees, so as we shot into it, we were shooting past the Alien on the pipes into the mirror reflecting the lead. So it looked as if we were shooting right down the pipes into the mold.”

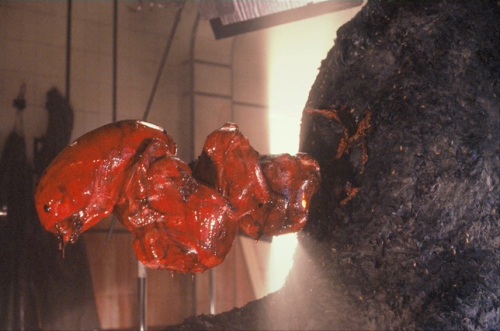

When water is poured on it, the quick cooling of the lead creates tremendous pressure on the Alien’s surface, before it explodes. The cracks that appear on its dome were created digitally by Boss film on a lead-covered puppet of the Alien. The head was digitized and the wire frame animatic of it was rotoscoped in order to track with the live-action head. The cracks were then drawn frame by frame, in black, on a flat sheet. The cracks were then scanned and digitally applied around the modeled head so that they could progress in perspective with the footage. The final shot was then digitally composited. The actual effect of the Alien exploding was achieved with a hollow creature model, moulded in flexible polyurethane. “It had a skin that was about three-quarters of an inch thick,” said George Gibbs, head of the pyrotechnic effects team. “We packed it with green blood and bits and pieces, and laced up the body with light grain primer cord and then set it off.”

In Alien³, Ellen Ripley ultimately sacrifices herself as the newborn Alien Queen inside her bursts from her chest. She holds the creature tightly as both descend into the furnace to their demise. Ripley first discovered the presence of the creature when she decided to perform a CAT-scan on her body; and previously, the Alien had refused to even harm her. In the first versions of the film, the reveal was to take place at the beginning of the film. For this purpose, ADI had built a puppet of the Facehugger proboscis and Alien embryo, and a model of Ripley’s neck. The sequence was eventually cut.

Additionally, the embryo was just another Alien embryo without defining characteristics, only to be later changed into a Queen. “It started off as just a creature embryo,” said Gillis, “and then it was later decided to make it a Queen embryo. So we had to go back and take a copy of our sculpture and make an appliance to give it the Queen carapace, the hood. It didn’t have the tiny arms like the adult Queen; but we thought, what the hell, maybe she grows those later.” Fincher had initially intended to reintroduce egg-morphing with his film, but the change from Warrior embryo to Queen embryo made the idea obsolete. ADI had started construction of the cocoons when the concept was ditched. “They were begun and then killed halfway through,” said Woodruff. “We were going to end up making about 20 of those cocoons, all vacuformed and stapled up. We started on two, and then the plug was pulled because Fincher’s idea was that the creature simply kills to eat. Actually we did finish one off for Fincher because he liked it so much. He had it on the set with him and would occasionally climb into it for inspiration. He called it his ‘thinking shell’.”

The Queen embryo is first seen in the CAT-scan sequence, for which a detailed, layered model portraying Ripley’s body and organs was sculpted and built. A larger than life scale model of the chest cavity hosting the Alien was also constructed. The latter featured a pulsating human heart and a rod puppet of the Alien embryo, complete with its own beating heart. “The embryo was made out of translucent urethane,” Woodruff told Fangoria, “and lit from behind gave it a glow that revealed the creature’s nervous [and circulatory] system, including its beating heart. We took the chestburster’s design and worked backwards, accentuating the head while making the arms and legs smaller.” Both elements were puppeteered by ADI crewmembers. An opening in the rear of the chest model was used to backlight the innards and the Alien, which were cast in translucent materials. Video Image Associates was hired for photography and image processing of the CAT-scan models, which were shot on a motion control system. The models were moved to suggest a rotation around the spinal axis — with “a sort of 3D, X-ray look,” according to crewmember Richard Hollander.

In Fincher’s original concept, Ripley would have sacrificed herself without the Queen actually bursting from her during the fall. Producer David Giler, however, opposed the idea and was adamant about having a payoff sequence at the end of the film. Edlund recalled: “the original background had Ripley falling into what was solely white and had her just dissolving into it. It was very stylistic and a much more cinematic ending. It was really quite beautiful, but David Giler came in and told us what he thought of it and that he felt the movie should be bookended by Ripley having a chestburster.” Edlund was otherwise satisfied by the change, saying that “to be honest, I liked the change. The audience kind of expects something like this and it was a payoff that wasn’t made with the original ending. The problem was that by the time the decision came down, we had only a little more than two weeks to shoot and composite three or four very complex bluescreen shots — important ones that affected the outcome of the movie and the way people would leave the theater thinking about it.”

Fincher opposed the idea but was forced to run with it. He said: “I never thought it was necessary to show the creature. We showed it to preview audiences and it was voted that we would do this. I was very much against this and dragged my feet and said, ‘I don’t believe in it, I don’t think it is important to see the Monster.’ No matter what cathartic experience we could expect from finally seeing the two strongest images from the first movie, the Chestburster and the character of Ripley, if we left the movie with her choking on her tongue then the audience would feel worse going out of the film than they do now. I said ‘whatever happens, she has to be a peace at the end. It has to be a sigh rather than gritting teeth and sweat.'” He also added that “it was vulgar. If she gets ripped apart before she falls into the fire, that’s not sacrifice, that’s janitorial service. To knowingly step into the void carrying this thing within her seemed to me to be more regal.” The original version of Ripley’s sacrifice was restored in the 2003 Assembly cut of the film.

For the final Queen chestbursting sequence, ADI devised an animatronic extension that attached directly to Sigourney Weaver’s chest. “We had a whole effect built where Ripley’s rib cage was spreading and then the Queen bursts out,” Woodruff said. “The articulated rod puppet [of the Queen] had moving arms and snapping jaws.” The new mechanism eliminated the necessity for a false torso, which, combined with the set up for the sequence, would have hindered shooting. The sequence was actually a very late addition to the film and was shot nearly a year after principal photography. “The first thing we had to do,” Edlund said, “was build a motion control seat for Sigourney that was split on the side so the camera could get in really close. We started on a tight close-up with her in an upright position. Then the seat tilted her back toward the bluescreen. When she was about perpendicular to the camera, the Chestburster was fired. Alec and Tom were on hand with nine of their Chestburster units. We went through seven of them — and after each take there was a major cleanup effort. It took a long time to get everything just right. Sigourney grabs the Chesbutrster and we go to a close-up and then back to a 14 inch rod puppet Ripley that Laine Liska made in one weekend and which we follow way, way down into the molten lead.” To enhance the dramatic weight of the scene, it was converted to a slow motion format in post-production.

Woodruff commented on the making of the effects: “a lot of our work, especially the new stuff that we were really enthusiastic about, got cut out. Being creature guys, we almost always would like to see more. But we realize there is a point where you can show too much and it gives away the illusion. I think we achieved a good balance.”

For more images of the Alien, visit the Monster Gallery.

Previous: Alien³, the Beginning

Next: Alien: Resurrection

Fantastic history of this process!

Sprecatissimo il Super Facehugger,così come si noti fin troppo come la marionetta sia stata mal inserita nell’ambiente circostante

My favorite version of the creature. Awesome article and thanks!!

Just discovered the website.Impressive piece, amazingly thorough and well researched. Picking up my jaw from the floor and placing it back af we fpeak.