Finnegan turns as the DANCE FLOOR and the D.J. BOOTH EXPLODE as SOMETHING RISES UP from below them. His eyes widen. And there it is — The huge, horrible, mutated, mucus-covered, sucker-faced HEAD OF THE CREATURE.

A giant mutated protoplasm. Jutting up from a breach in the floor. The trunk of the Creature, the part where all the Tentacles come from is below the next deck. A slimy, translucent MEMBRANE slowly RISES, REVEALING what appears to be some sort of ORGANIC LIQUID EYE.

This is how the massive, unidentified deep sea Beast is finally revealed in Stephen Sommers’s and Robert Mark Kamen’s script for Deep Rising. In the climax of the film, it is revealed that the multiple worm-like entities infesting the Argonautica are actually the tentacles of a single, gargantuan Monster. Bringing the abomination to the screen was a task assigned to Dream Quest Images, the visual effects division of Walt Disney Company, and Industrial Light & Magic, for a limited number of shots. Dream Quest Shop supervisor Mike Shea had first to ‘cut down’ the original script, which conceived an unreachable — for the time — effects complexity. “When we first came on board in October 1995,” he told Cinefex, “there was a draft that called for some 500 effects shots. We were able to devise Steve in terms of what could and couldn’t be done, and assist with some of the early script rewrites.”

Rob Bottin was hired as the film’s main creature designer. “Rob Bottin was great to work with,” said Mark Alfrey, one of the sculptors. “because he never held my hand. He usually likes to give you inspiration — he would sit and talk for an hour about what needed to be sculpted. Then he let you go where you could go.” Concept art for the creature was devised by Carlos Huante under Bottin’s supervision. An 8′ tall maquette of the monster was built and used to pitch the project to the Disney Studio chairman — along with some animation tests, “to show him what we thought this creature would look like, how it would move and why he should spend a lot of money on an octopus tentacle that basically chases a bunch of people down a hall.”

A team of digital effects artists, led by Dan DeLeeuw and creature supervisor Rob Dressel, conducted months of research, and created an initial ‘proof-of-concept’ test. DeLeeuw recalled: “we were expanding our studio at the time, and we had a room that wasn’t done yet, with a bunch of exposed pipes that proved ideal for simulating the ocean liner’s engine room. We went in and gooped it up and shot that as a background plate.” With an early iteration of the creature design, the team animated a short sequence in which a digital tentacle, coiled around one of the pipes, drops down and reaches violently for the camera. Shea commented: “it took quite a long time to get that test done, but I think it was a turning point for Steve. It was like: ‘well, okay. Now I know what I’m getting into.'”

Sommers initially wanted to use a majority of practical effects, with an animatronic tentacle scheduled to be built. The digital counterparts were to be implemented only for the more visually complex sequences. After the first Computer Generated test, however, the director eventually decided to use digital effects for most of the scheduled sequences. DeLeeuw said: “when we started, we were looking at producing a digital version just for distant views, and shots involving a lot of movement. The idea was that our work would be complemented by some kind of practical rig — an actual twenty-foot-long tentacle that they would have on set — for all the closeup stuff, and for any scenes involving interaction with the actors. But as we progressed, and the production began weighing the costs of building and shooting a full-size beast on set, everything started to go digital and we ended up taking on the preponderance of the creature work.”

Sommers initially wanted to use a majority of practical effects, with an animatronic tentacle scheduled to be built. The digital counterparts were to be implemented only for the more visually complex sequences. After the first Computer Generated test, however, the director eventually decided to use digital effects for most of the scheduled sequences. DeLeeuw said: “when we started, we were looking at producing a digital version just for distant views, and shots involving a lot of movement. The idea was that our work would be complemented by some kind of practical rig — an actual twenty-foot-long tentacle that they would have on set — for all the closeup stuff, and for any scenes involving interaction with the actors. But as we progressed, and the production began weighing the costs of building and shooting a full-size beast on set, everything started to go digital and we ended up taking on the preponderance of the creature work.”

Eventually, the only practical creature effect was represented by a single insert stunt tentacle, used in a total of two shots in the entire film. The lack of practical effects also allowed the animators to have more freedom, without having to match the digital creature’s movements to the animatronics.

The script for the film provided vague portraits of the creature — who was nicknamed ‘Crusty’, after crustacean, by the effects team — with the tentacles described as “black and veiny,” thick, and leech-like. “The TENTACLE slowly SQUIRMS across the wall like a big leech,” the script reads. “Trying to find its prey. Finnegan is frozen in place. Watching. Trillian sits up, eyes widening in fear as she sees — Hideous little worm-like FEELERS and SUCKERS protrude up and down the Tentacle. WRIGGLING and WRITHING and feeling their way across the wall.”

Wide creative liberty was allowed for the design team. DeLeeuw commented on the process, saying that “we were really inventing a new organism, so we needed a history for it.” The creature went through numerous design iterations, including arachnid-like and crustacean-like incarnations. Rob Bottin and the crew finally envisioned a creature that would bear the traits of both snakes and octopuses, with the striking attitude of the former and gelatinous consistency of the latter. Reptiles and marine animals were the main natural references used for the design.

In particular, the vampire squid served as the main source of inspiration for the tentacled beast. The crew saw footage of the animal in a National Geographic documentary, titled Incredible Suckers. DeLeeuw said: “it had webbed tentacles, and, for self-protection, could actually turn itself inside out by opening up its web and wrapping it around its head. Instead of suckers, it had little teeth; so when it opened up, it turned into a giant ball of fangs.”

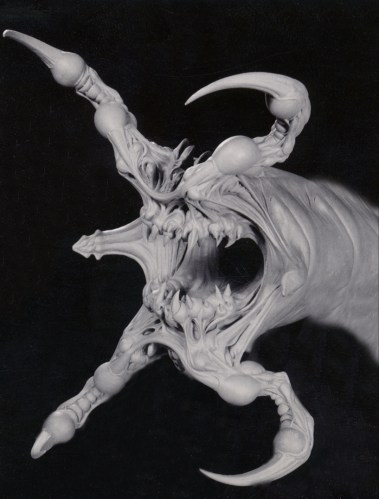

Bottin’s team sculpted the ‘tentacle-end’ head design, creating three maquettes with distinct phases of the head splitting open: in the first, ‘idle’ pose, the tentacle is closed, showing the interlocking teeth; in the second, the tentacle begins to split open, revealing the internal structure; in the third, the head is fully open and the internal jaw is exposed. The maquettes were scanned and used as bases for the digital model of the tentacle. Shea explained: “we found a scanning tool that would get us down to one-millimeter scanning credit, which allowed us to capture all the intricacies of the original clay models. One of the things we had done during preproduction — while still under the impression that we would be matching our creature to an animatronic counterpart — was develop a way to use all the scanning data so we wouldn’t have to regenerate everything Rob was doing.”

Bottin’s team sculpted the ‘tentacle-end’ head design, creating three maquettes with distinct phases of the head splitting open: in the first, ‘idle’ pose, the tentacle is closed, showing the interlocking teeth; in the second, the tentacle begins to split open, revealing the internal structure; in the third, the head is fully open and the internal jaw is exposed. The maquettes were scanned and used as bases for the digital model of the tentacle. Shea explained: “we found a scanning tool that would get us down to one-millimeter scanning credit, which allowed us to capture all the intricacies of the original clay models. One of the things we had done during preproduction — while still under the impression that we would be matching our creature to an animatronic counterpart — was develop a way to use all the scanning data so we wouldn’t have to regenerate everything Rob was doing.”

Photographs of the sculptures were also used as reference for the creature’s complex texture and color scheme (“they wanted a squid-like surface,” Dressel said) devised by John Murrah. In order to obtain the slimy and organic quality of the fully-rendered Monster, Alias wavefront shaders were used to organize several hand-painted textures into layers. Dressel commented on the process: “with CG, anytime you want something shiny, you have to beware of the curse of the plastic look. So we utilized a base layer to define the color and contours of the creature, and then a second layer to define the specular light that shined off of it and to add additional texture.” Warp lights were used to distort the geometry, moving the skin slightly to enhance the impression of a slime-covered surface.

Even before the creature design reached its final appearance, the animators had already begun experimenting with its movement. With Alias Wavefront Power Animator as the main tool, they devised a digital serpentine skeleton, structured like a chain or a spline, moving in a fluid manner. Dressel explained the features of the model: “with a spline, the control points serve as animation handles. As we move the handles around, the spline changes shape and can be put into very exacting poses. But with a spline, there is no fixed length. As soon as you move a control point, the length of it changes –it’s an infinitely stretchable entity — whereas our creature was not. Although there were some stretching and compression, it had to feel solid and heavy and grounded. So our animators had to be very aware of that and keep the volume and mass and length of the creature the same as they worked through it.”

Another element that made the animation process more complex was Sommers’ concept of a creature that, despite its size, could fit within very small passages (much like an octopus), such as corridors and vents. Shea recalled: “we spent a lot of time developing a way to do that. One of the biggest issues we fought all the time was the speed at which the creature was moving. We needed to give it weight and muscle, but we also needed to make it fast — a factor dictated at times by the sequence of practical effects that was happening on set.” Chris Bailey was hired as a creature consultant, in order to help determine weight, speed, and coherence of motion.

The last element of the creature to be brought on film was its actual head, sculpted with its mouth opened, by Rob Bottin. Dressel recalled the animation process: “no one knew how the mouth closed or what it did. So Eugene Jeong — who pretty much masterminded the big head model — added bone structure inside that worked like a human jaw, but with interlocking layers of teeth that made it look like a giant mouth from hell closing in from every corner.

The creature’s eyes were changed from the script, which portrayed them on the end of specific sensory tentacles. Designed again after the vampire squid’s eyes, they are of a semi-transparent, blue tone. The circular eyelids’ movements were inspired by the iris of a camera. When it is shot, the explosion was obtained with a practical explosion of a latex membrane filled with methocel — and stretched across an eye-shaped opening in a piece of plywood. The element was filmed in slow-motion and then composited over the digital eye. Another trait inspired by octopuses is the system of valves on the sides of the Monster’s head — achieved with 3D warping techniques.

The creature was finalized with digital saliva dripping from its mouth and other parts. “We used geometry to make strings of goo stretched between the teeth,” Dressel said. “Getting a piece of goo to stretch out is one thing, but to get it to break and look natural in CG is not always an easy task.”

As a piece of trivia, the effects crew actually ‘cheated’ when it came to showing how the tentacles were attached to the head portion of the body. “We did kind of cheat,” Dressel said. “There’s a bunch of debris wrapped around the hole in the ship’s hull that the head emerges through, and the tentacles just curl up over the top of that.” Shots of Finnegan grabbed by the creature were achieved with the actor lifted by a crane — which was erased and replaced with the tentacle.

Test audiences were confused as to whether the creature was killed by the explosion or not. To erase all doubts, the Monster meets a fiery and gruesome demise in the last digital sequence created for the film — where its head is seen blown apart by the blast. A blistering texture was created by Jeong for the shot where the beast is engulfed in flames. When the creature explodes, its insides were achieved with a mixture of digital and practical effects.

Shea ultimately commented on the experience, saying that “I am proud of Deep Rising and what we accomplished. I believe we created something that was truly unique and that holds its own with most of what’s been done. Those were my goals, and we met them.”

For more images of the Monster, visit the Monster Gallery.

For an in-depth retrospective on the ‘half-digested Billy’ visual effects sequences, visit this VFXBlog article.

Now what?

One of my all-time favourite movies, it’s a riot from beginning to end. Thanks for the article!

Awesome movie!

I’m hoping that “Harbinger Down” will bring back practical effects in a big way for monster movies-have you covered that here yet?

It has not been released yet — so I cannot have!

Just LOVE this site! Keep it up guys and gals, great work!

Watched this plenty as a kid. Favorite scene doesn’t really involve the monsters though. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3WmHwScNyMk

[…] ▲1998年電影《Deep Rising》的八爪魚怪物官方概念圖(連結) […]