In approaching the design aspects for Alien: Romulus, director Fede Alvarez started from the baseline point that everything should be reminiscent of the first two Alien films. Of course, that implied that the iconic stages of the Alien life cycle present in the film should harken back to the very first Alien and the terrors of Hadley’s Hope. “We’re trying to take the designs back to the original concept,” said Alvarez. “We do embrace the biomechanical aspects of the creatures that were abandoned at one point. There was something about that that I find fascinating and scarier than if it’s just an organic creature.”

Returning from the previous film, Dane Hallett acted as the lead creature design artist, joined by the art departments at Framestore and Double Negative (DNEG). The production also brought forth an ensemble of companies, many of which had already contributed to the series beforehand; three main houses provided concepts and practical creature effects: Weta Workshop (for the Facehugger), Studio Gillis (for the Chestburster), and Legacy Effects (for the cocoon and the adult Alien). On the visual effects front, digital creatures were devised by Industrial Light & Magic, Image Engine, and WetaFX.

As a baseline, Alvarez intended to shoot as much as possible in-camera. “His mantra was whatever he could do in-camera, that’s what he wanted,” Legacy Effects lead Shane Mahan related, “because he prefers the rich tactile sense on film, the look of it. He would say, ‘if we could do it in ’79 and ’86, we can certainly do it now.'”

Certain development processes were streamlined by new pipelines. These include digital sculpting, as well as advanced 3D printing. All the practical creatures — be they from Weta, Studio Gillis or Legacy Effects — were first sculpted in zBrush, with their mechanics developed in AutoCAD and similar programs, 3D-printed and then cast. Mahan elaborated: “the fact that we sculpt in a computer, and rapidly prototype and print full-scale sections of bodies, as opposed to sculpting entirely by clay and making molds, [means] we can engineer the mechanisms first and then skin them with the digital sculpts afterwards. I mean, you don’t have to retrofit the mechanisms into the art. We can work around it and bypass a problem. There are so many things that we can do, on a shorter production timeline, using the technology that’s available to streamline the process. People don’t realize just how much we use digital work on our side of things to create physical effects. We don’t do CGI shots, but we’re using an awful lot of digital technology to create the creatures. There’s still a great deal of hand sculpting, absolutely, for prosthetic makeups and certain things that you need to have actual clay-to-surface construction, but the advancements are tremendous. Also, with telemetry-driven animatronics and very strong servos and computer systems that run those things, everything is really quite spectacular today.”

On the visual effects front, not only the digital creations had to match the practicals, but also had to be convincingly integrated within the photography, whose director Galo Olivares championed backlighting and rich contrast. Visual effects supervisor Eric Barba said: “matching Galo’s lighting style was one of the most rewarding and demanding parts of the project. We had to ensure the digital creations didn’t just blend into the live-action shots but felt like they were lit by the same haunting glow.”

To that end, Barba adds, “we’re always taking notes on the way things are lit, looking at how Galo did things. Our onset team shot tons of HDRIs and set photography so that our visual effects partners could help. HDRIs were taken from those positions so we get the same quality of light captured. When the CG teams put the characters back, they’re able to sample that actual lighting and get the same color tone and dynamic range. Then it’s trying to match. The dynamic range is what makes it work when highlights get bright and get the blacks falling into nothing because Galo liked to let it go that way.”

A long process of trial and error was involved. “Artistically, getting CG and compositing artists to match the look of what Galo did took a long time,” Barba continues. “It took versions, trials and errors, and less is more. We tend to over-light things in CG because we make all these wonderful things and people want to see what they’ve done.”

In the opening of Alien: Romulus, the original Nostromo Alien is (somehow) retrieved from the wreckage of the ship. The creature is encased within a rock-like formation of its own secretion, devised both as a full-size prop and as a digital effect, based on concept art by Hallett. “I explored a ton of variants until finally sculpting one in the garage and […] it finally won,” said the artist. In the end, in order to get the shape just right, I boiled a Neca figure in a pot of water til it was jelly like. Then, I bound it in rubber bands and cling wrap before smothering it in monster clay.”

Rather than articulating the rampage of the creature aboard the Renaissance ship, the film only shows its aftermath, with a dead Alien hanging from a ceiling hole. The decomposing corpse was a practical Legacy Effects creation — sculpted by Mahan and others — a faithful replica of the original design, appropriately damaged with wounds and missing portions of its body. Further damage was added in post-production, with the removal of a large portion of the right leg.

For the rest of the film, the creatures that appear are imperfect clones of the Nostromo Alien, and as such, were given a slight degree of freedom in their design, while maintaining high fidelity to it in their anatomy and features. Extrapolating from Prometheus and Alien: Covenant, as well as multiple expanded universe sources — such as the novel Aliens: The Cold Forge, where the function and the name Plagiarus praepotens was introduced — Alvarez also wrote the black fluid pathogen into the story, having it as what the Facehuggers implant into a host to grow a Chestburster. “The Xenomorphs come out of that thing [the fluid],” he said, “which means it has to be inside them. It’s the Xenomorphs’ semen, almost.” This is a revision of the life cycle, as there was a previous mention — by Bishop, in Aliens — of “embryo implantation”.

Weta Workshop was already devising practical Facehuggers for Alien: Earth when the team was hired for Romulus — something that gave them an edge. Concept art — in the form of paintings and digital sculptures — revised the Facehugger design in slight terms, endowing it with new textures, as well as a different underside from which the proboscis is everted. Rows of barbs were added to the leg tips, much like the Queen Facehugger — and, coincidentally, a fulfillment of Roger Dicken’s criticism of the original creature. While initial concepts maintained the opaque yellows of the original Facehugger, the colouration eventually steered towards darker tones. Hallett commented: “the darker ones kept rising to the top of the selection pack until it was the chosen one. The theory being that these ones incorporated some the black pigment found in the Xeno.”

Construction of Facehuggers puppets and dummies was led by Richard Taylor, Rob Gillies, Cameron May, and Joe Dunckley. After a script breakdown, it was determined that several different versions with specific purposes were needed, with the final count at 73; some sequences ultimately employed over 40 at the same time. Generally, the Facehugger puppets and dummies’ skin was cast in silicone, with foam latex for the tail in some cases, and silicone-reinforced rigid nylon on the legs — for reasons of durability and access. May explained: “we were trying to get the legs to be as spindly as possible. We went about that by making the legs hard surfaces to get more real estate inside the legs to work with mechanically. We made those sorts of decisions quite early on.” Other, more durable materials were employed when additional weight was needed. Internal mechanisms for the creatures were designed digitally and then 3D-printed.

A servo- and cable-controlled hero animatronic was fully articulated, and piloted by a single puppeteer through a tablet and two joysticks. May explained: “we designed different kinematic gaits for the Facehugger and then had joysticks that could override those individual commands.”

In fact, a motion language was developed for the Facehuggers, based on previous films and on natural reference. May said: “one thing that we noticed early on is that so much of the language of the Facehuggers was not about perfect control, but actually quite aggressive random articulation. So, we still had to have some of that kind of language in the way that the Facehuggers operated because that’s part of their history in terms of how they look and feel on screen.”

Remote control Facehuggers could scuttle across the floor, largely based on the running puppet from Aliens — but instead of a pull toy-type mechanism, they were built with a structure similar to an RC car. May related: “the things that we added to the mix were a pair of brushless motors, some wheels, and an RC remote. The motors were then attached to the legs on each side of the body. So, if the runner ran forward, the legs ran forward; if it ran back, the legs ran back.” A wheel mechanism on the underside connected to the base of the legs, making them dependent on its roll. An individual geared motor drove the frantic movements of the tail. Dunckley commented: “what was really good was that as they were moving, the tail dynamics came naturally. The foam latex just bounced around beautifully. It’s kind of scarier that the tail is erratic, that it’s lashing around. When it connects to someone, that’s when it gets dexterous. That’s when it knows what it’s gonna do.”

A swimming Facehugger was developed for the scene where one of the creatures leap out of the water to attack. The puppet had to fit the director’s specific requirements for the sequence: a continuous shot of the creature in the water, which culminates in a leap. The conundrum was solved with the creation of two distinct puppets, which were filmed in tandem — with a framing trick that would give the impression of a singular element travelling across the shot. The engineering department first devised a submerged track on a winch that would drag the first Facehugger along, with the swimming motion “translated through a mechanism as it traveled along the rail,” May explained. “On the rail, there was a wheel that was picking up the linear motion of the rail, translating it to rotary, and then there was a cam mechanism, which just essentially flipped the tail around in the water. It was a simple, old-school method, but it worked really well.” The swimming Facehugger puppet — with a core of urethane foam for appropriate buoyancy — disappeared from the shot through the lower side of the frame. A second puppet, at the end of the rail, was synchronized to leap out of the water at an appropriate time.

Attack Facehuggers were devised with different functions and purposes. The special effects team employed reverse photography, much like in Aliens. Dunckley recalled: “we planned on using reverse photography, since sticking the landing would be a difficult thing. We did some tests in-house, starting with a Facehugger attached to a victim’s face with the tail wrapped around the neck. We had spring-loaded fingers so that it’s got tension on them.” Puppeteers could release the leg tension and pull the Facehugger away from the actor; played in reverse, the footage would display the creature’s attack. This expedient allowed a more accurate, lifelike and violent landing, not to mention a more safe set-up for the actor involved in the scene.

One key sequence involving — at first — an attack Facehugger was Navarro’s impregnation, where the creature successfully latches onto the character’s face, only to be removed shortly after, with its proboscis being slowly pulled out of Navarro’s throat and through her mouth. This graphic effect was achieved with three different proboscises: the first was mechanized, able to perform a wide range of movement; the second was retractable, able to be everted and withdrawn from the underside orifice; the third was a more elaborate version for the pullout effect. Dunckley explained: “the real challenge was that Fede wanted to see — as they were removing the Facehugger — he wanted to see the proboscis being pulled out of the throat. So, what we did was, we had one that was hollow silicone, and we had just a bent piece of stainless steel in the correct shape with a little loop on the end. We then turned the proboscis inside out and lubed it up. As it’s being extracted, we could extend the steel loop, inflating the proboscis so it would look like it was coming from her throat.”

The so-called “comfort huggers” could be worn around actors’ faces. Cables within the performers’ costumes controlled the inflation and deflation of the Facehuggers’ breathing sacs; puppeteers rehearsed with the actors for a proper synchronization. Threads on the creatures’ tails could be pulled to tighten their grip around the actors’ necks.

Other Facehugger puppets included stunt dummies that could be safely thrown at actors; specific crawling puppets for when the creatures are encased in the cryo chambers and then escape; and dead Facehuggers for the hive set piece, in various stages of decay. Dunckley commented: “we had such a vast range of them, and it was really Fede’s insistence that he wanted to approach this in a practical manner that enabled us to get that specific on our builds. You don’t often get the time to approach practical effects with the correct amount of rehearsal time and build time. So, from that perspective, it was a real pleasure, really unique.”

Even with the great variety of puppets, some more complex actions — such as the chase sequence — were mostly performed by digital Facehuggers, devised by ILM. As they often had to appear in the same shot as the practical creatures, they had to be an exact match. While earlier films were used as reference, the animation team was not restrained to them — endowing the Facehuggers with more fluidity.

ILM visual effects supervisor Nelson Sepulveda-Fauser related: “in some cases, when we saw that action of the Facehugger on set, it was obvious that it was a puppet. Although that was desirable in many cases, after a while the director realized this sequence was not going to be super exciting with things on wheels rolling along chasing these guys. So, we had to work out different hugger run cycles for the chase. That took some time and experimentation, because it needed to both look like a mechanical thing, so it could pass as practical, and also it needed to follow this very specific action that the director wanted. We went through tons and tons of experimentation on how to make that work and, finally, we landed on something that Fede was really happy with, because they still look like they could be animatronic. We always kept it to some grounded reality.”

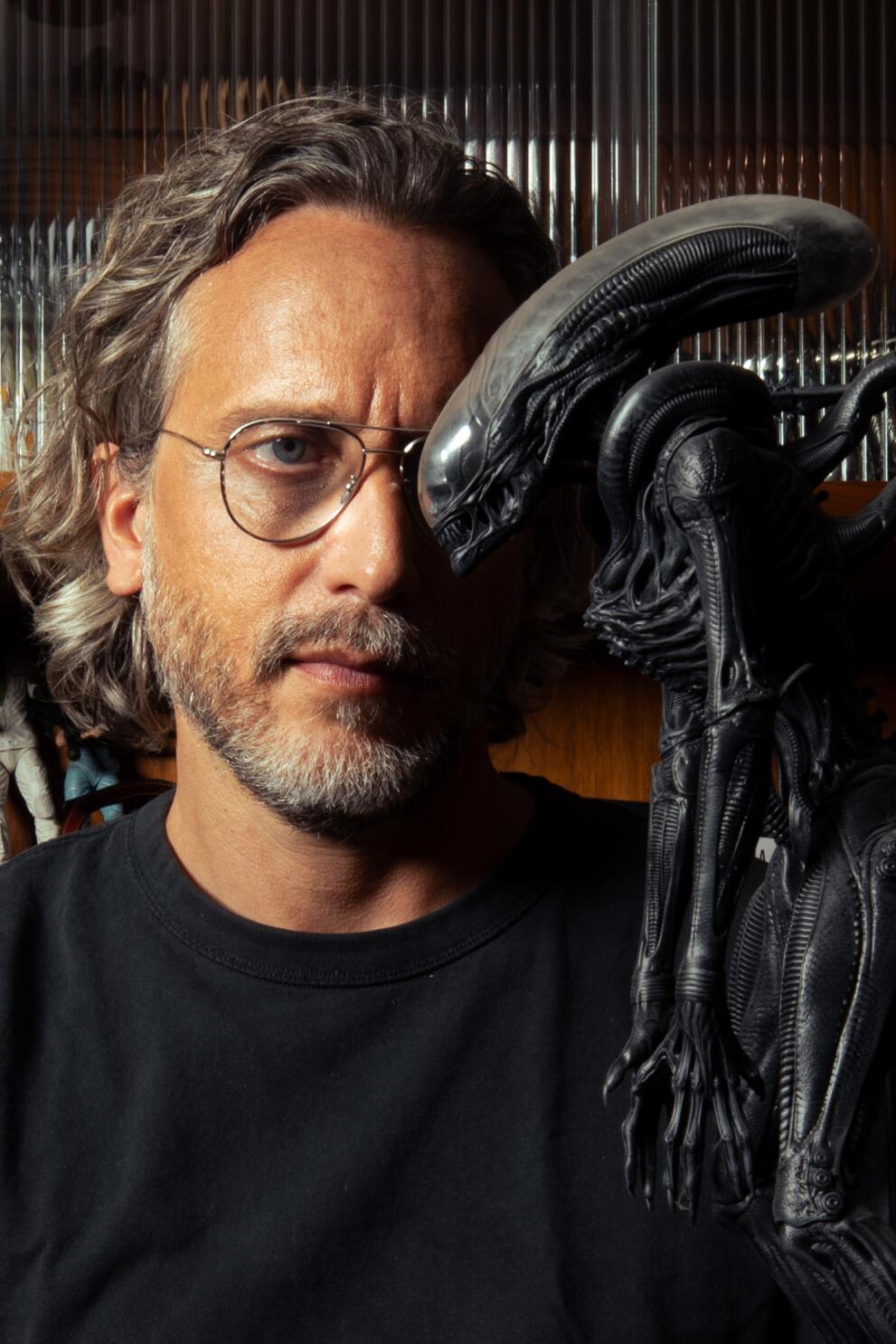

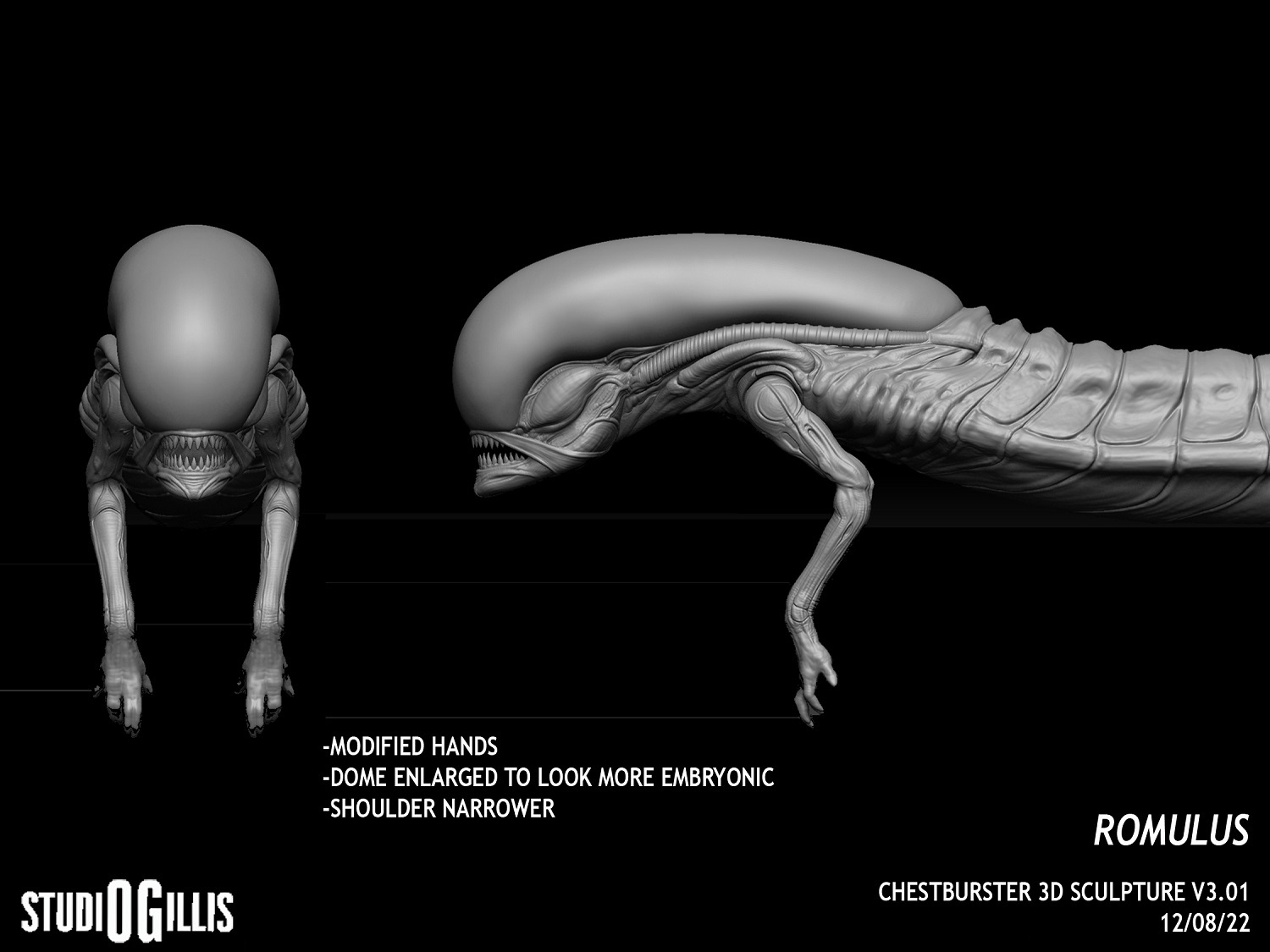

Design and practical construction of the Chestburster was assigned to Studio Gillis, Alec Gillis’ newly opened special effects shop after the closure of Amalgamated Dynamics. Hallett’s concept art — dubbed by the artist the “Nymph” burster — initially explored new options and configurations, including the suggestion of developing limbs under the skin. Hallett related: “I adore the original burster design, and stepping into its shadow was a genuinely nerve-wracking experience. I wanted to ‘add’ to it without taking anything away. The burster in Aliens introduced fully-formed arms, but I wanted to take a more spiritual approach. I aimed for something more insidious and foreboding in nature — less literal. Pregnant with explosive violence. […] Also, I wanted this version to foreshadow rapid growth and elongated features that would eventually grow into the Big Chap.” Eventually, the design turned to a more conservative approach, with two small and thin arms — like the Chestburster in Aliens. The developing dome was made more prominent and bulbous to evoke a more embryonic state.

The design was further refined by Studio Gillis, and then translated into a digital sculpture by Mauricio Ruiz. The segmented mechanical understructure developed in AutoCAD, based on the Aliens version of the creature. “That 3D model went straight to my mechanical designer, David Penikas,” said Gillis, “who could start designing all the mechanisms in 3D. He didn’t have to wait for a mold to be made or a core to create the skin. I impressed upon him that we needed to have a more fluid and more organic mechanism than we’ve had in the past. He did a terrific job of it, alongside Zac Teller, with the animatronics.” The skin was cast in silicone, with diecast teeth.

One detail that Alvarez wanted to see was the Chestburster developing in real time, even with its rapid pigment shift. Gillis initially thought such effect would be achieved digitally, but the director insisted on it being an in-camera, practical effect. Gillis was inspired by bleeding Halloween masks, wherein fake blood could be pumped in the space between two plastic layers. Of course, the Chestburster would be more complex: a separate transparent dome was applied; black fluid could be injected to coarse under it. Gillis explained: “we have the clear dome on the head, so that affords us an opportunity. We cast it out of a very clear silicone, so it was a separate piece on the top of the Chestburster’s head. Naturally, there’s a little air gap between one part and the other. Nick Reisinger, on my crew, who’s very clever, was able to put tubes into it so that you’d have a tube that would pump clear water in between the dome and the head. Then, we inject black acrylic paint into it, so it sort of clouds over. And then we could suction it out, and we could keep it going. You could do like a heartbeat effect. It was very expressive.”

Upon seeing tests of this effect, Gillis became concerned that it would read to audiences as digital, rather than practical. “It was very gradated and smooth,” he said. “It lacked an organic, you know, chunkiness or something.” This issue was solved by devising a capillary system through which the coloured fluid would be pumped, to add a more organic pattern.

The special effects team initially built cable-controlled Chestburster puppets with a size consistent with the other films’. Alvarez, however, thought that they looked disproportionate in comparison with Aileen Wu (Navarro). “In the end, our Chestburster is about half the size of a traditional one,” Gillis said. “I actually thought, ‘well, that fits the story. If we’re compressing the time that it all happens, maybe this creature is like a premature birth.” Scaled-down puppets were thus devised in a relatively short time, due to them coming from a digital source. “Here’s an advantage of sculpting in 3D in the computer,” said Gillis. “I can print up whatever size I want and change it to the director’s desires. And it worked out really well.” The larger Chestbursters would still find use for extreme close-up shots.

The chestbursting sequence starts with a complex, layered digital effect of the creature within Navarro’s chest — revealed by a futuristic x-ray wand. “We digitally-built all of Navarro’s skeletal, muscular, circulatory structure, as well as organs,” said Sepulveda-Fauser. “We researched the look of an x-ray, and we worked up the ideas in compositing, with animation to match the original puppet, broke some ribs, and popped it through. It was a quick moment but pretty neat.”

This idea was engineered not to repeat the original films, giving a new spin on a staple moment. Sepulveda-Fauser continues: “you kind of know what’s going to happen, but you actually don’t know what’s going to happen. The reveal of the creature from the inside was a great idea. That was the scary moment — understanding this thing is ready to pop out. We weren’t repeating the original, we’re scaring you in a slightly different way, and I thought that was really cool.”

When it came to the actual burst, Alvarez suggested to take a different approach compared to previous iterations — comparing it to a human birth. Gillis recalled: “it was intended to be a lot less explosive than it has been. I thought that was a really great way to ground the effect. Even though it’s not explosive, it’s more like a slow birth. It’s a little more grisly, in a way. I liked that Fede was interested in giving this Chestburster some time to live and breathe and be alive.”

For the emergence of the Chestburster, the actress was laid on a slant board, with a fake silicone torso — created by Iván Pohárnok — on top, blended onto her neck. An element suggested by Hallett was an amniotic sac that initially encased the Chestburster as it slithered out. The artist related: “I first explored that the burster might appear inside its amniotic sack after birth, and then slide out. Sort of like, at first you weren’t sure what kind of burster it was, then it peaks out and we’re (hopefully) doubly grossed out. Fede loved the idea and so it ultimately made it into the final cut.” The sac was made of wet hose cloth, and pulled away by thin cables. For close-up shots, the larger Chestburster puppets were employed alongside an appropriately one-and-a-half scaled fake torso.

In previous Alien films, what happens between the Chestburster and adult Alien stages had been left to the audience’s imagination. In an attempt to solve that question, Alvarez decided to feature a sequence where the characters stumble upon a cocoon that would reveal a subadult Alien. Mahan related: “it may be a new life cycle that Fede has created for this story, and if it ever happened in the other films, behind the scenes, we never saw it happen — but this was our moment to kind of recreate the mystery and the energy of John Hurt looking into the egg from the first film. That’s how we approached it.”

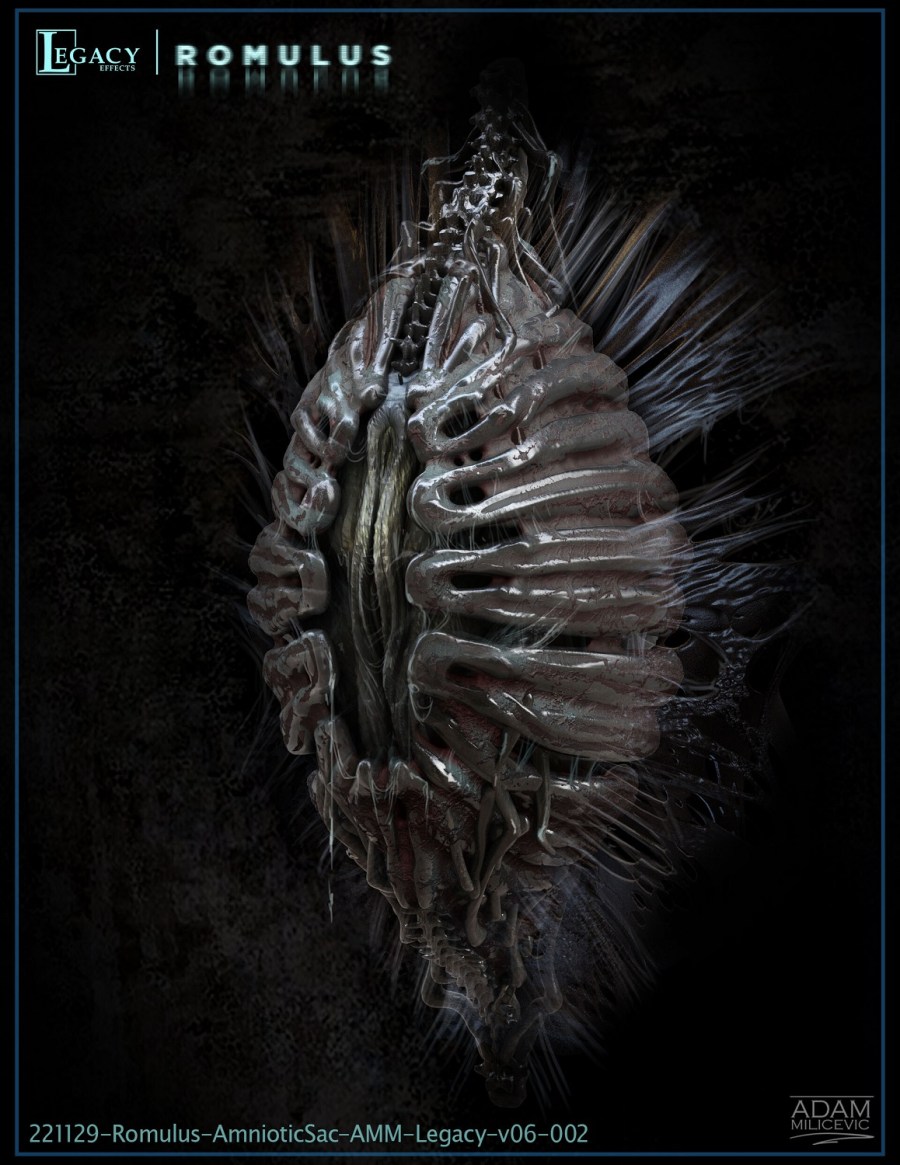

Hallett started from referencing — on a purely visual level — Giger’s concept art of the digesting Egg hosts for the original film, as well as insect pupae, and human amnotic tissue and placenta. After several variations that he thought were not going anywhere, the artist hit an empasse. “I was choking on the cocoon shape, trying to get it just right,” he said. “After many drawings, I sculpted one out of frustration, photographed it, then painted over it.” The paintover was further developed by Adam Milicevic at Legacy.

Two cocoons were built by Legacy: one with limited cable-controlled motion of the external rib-like projections and the central vaginal shape, and one to allow the emergence of a performer in an Alien suit (discussed later). “[The] secondary suit was for the birthing scene,” said Mahan. “That moment needed a lot of dexterity to come out. The best way to do that was with a suit actor.” For some shots with subtler movement, the practical cocoon was replaced with a digital replica by Image Engine FX.

Hallett, joined by a number of other artists — like Jerad S. Marantz and Andrew Baker at WetaFX, and Antony Nguyen at DNEG — initially explored a number of variations on the adult Alien design. The concepts experimented with different head shapes, textures, various degrees of translucency, but eventually gravitated towards something more reminiscent of the original Giger design. Nguyen’s digital concept sculpture seemed, in particular, close to the direction Alvarez wanted.

The produced material was brought to Legacy Effects, where design concepts were developed further by a team comprising of Scott Patton, Savannah Suderman, Darnell Isom, and Adam Milicevic. Mahan said: “we wanted this film to feel organically new, but to also feel familiar. I think when people think of the original film, the classic thing is the traditional long head that was created, and certainly the silver teeth, and the subliminal skull, which had been gone for a while from the Xenos from some of the films. We wanted to bring some of those elements back but play with the surface texture so it wasn’t just shiny and smooth. We didn’t want it to just feel like electrical tubing, hosing and mechanical parts.”

Points of reference at this stage also came from Giger’s art and James Cameron’s Alien Queen — attempting a subtle visual connection. Mahan related: “we really wanted to pay tribute to Giger’s paintings and his artwork. We also wanted the Xenomorph to feel like an offspring of the Queen, even though in the context of the chronological order of the films — this falls between Alien and Aliens. You haven’t technically seen the Queen yet, but if you look at the two together, there’s a familiar trait of the Queen in our Xenomorph, in the very narrow torso. The tails have always had a bony structure to them, but that’s also another artifact of the Queen. The tail is very Queen-like.”

Another element Alvarez wanted was sharp skin — like a shark’s — with translucent areas. Mahan said: “he wanted it to be very rough and sharp. His description was that ‘even if you ran your hand along it or if it bumped up against you, it would cut your skin,’ so there’s a lot of ridges and sharp points to it, and the overall feeling is just very dangerous.” Legacy Effects lead Lindsay McGowan added: “Fede wanted it to feel like it would be like having little razors cutting you. We added beetle-like texture to the surface of it per his request, and I think it really worked really nicely.”

The new Alien design was finalized in a digital sculpture by Scott Patton and Darnell Isom. In the film, a subadult Alien emerges from the cocoon, and a second sculpture was devised with different proportions, such as shorter back pipes. While concept art by Hallett explored variations of the head wound on Scorched (or Sparky, as nicknamed by the visual effects crews), the final version was simplified to a burn scar on the front of the dome, allowing for easy parts-swapping for different Alien characters; in post-production, Scorched’s scar would also be augmented in post-production with digital spark elements to highlight the biomechanical nature of the character.

Both sculptures were first printed as small scale maquettes to convey how they would look in a real environment. The subadult Alien displays certain blue hues, again reminiscent of the Queen, while the adult has a more black-based colour scheme. McGowan said: “from Alien³, the Xenos had become much more brown in tone, and we wanted to get back to the dark, imposing, bug-like aspect of it. Fede was all about that.”

Construction of all versions of the creatures was led by Lindsay McGowan, Alan Scott, and Shane Mahan. The latter’s experience on Aliens proved particularly useful. “You keep a mental log book of things that worked,” he said, “and things that you wished you could have improved upon just because of the technology or the materials at the time. So much has happened since 1986 in terms of translucent, flexible materials.” Each Alien puppet started from a 3D print of the model, which was refined with hard surface modelling and then moulded. The skin was cast in urethane, silicone and foam latex depending on the requirements of the specific parts. Ryan Pintar and Parker Hensley were responsible for the overall painting.

Translucent elements were introduced into puppets and suits — such as clear silicone panels in the face, arms and legs — to further sell the illusion that the creatures were not people in suits. The back pipes were also translucent. “When the light catches those,” said McGowan, “you can see through it a little bit. And that was a first for the Xeno.”

Hero animatronics were built with full articulation. They were hydraulically operated, and mounted on a mechanized gimbal. For a more lively performance, parts of the creatures could pulsate or vibrate. Mahan said: “Fede wanted parts of the creature to move, to just shudder and not just be this stiff thing. So, the neck is pulsing. We had a device in the rubber neck to make it vibrate. Something similar to what we accomplished on the Queen in Aliens.” To keep the weight down, the surface relied on urethane. Mahan explained: “we cast very lightweight urethane castings to keep the weight of the animatronic down. It was very thin. It’s got kind of an exoskeleton feel to it, and it could shell over the mechanics very easily. It paints very easily. It just has a great sort of carapace, insect-like registration to the eye when you see it. The whole thing’s conducive to the feeling of a chrysalis insect, a beetle’s shell.”

One element not seen in the final film is an articulation of the front of the head, similar to Carlo Rambaldi’s early animatronic heads for Alien, as well as the Alien Queen — which the Romulus version was based upon. Mahan explained: “the Xenomorph’s head has always been this long, stiff piece, so where the jaw is, we added a joint that moves the front of the face side to side, which is really cool. That’s kind of reflective of the Alien Queen.”

Bunraku-type puppets were cast from the same moulds as the animatronic. They were lighter in weight, with simpler mechanisms. This added a certain degree of freedom for specific movements. “We could make that walk, we could make it run,” said Mahan, “we could make it squat down to the ground, we could make it pursue people. Full walking leg motions are hard for an animatronic because of the weight. You can make the animatronic look as though it’s walking when you put it on dolly tracks and things like that. But you have to set those shots up and plan it out.”

The Alien suits — one for the subadult Scorched, one for the adult — were designed to fit performer Trevor Newlin. They were mainly used for shots that the animatronic could not perform due to its weight, such as the emergence from the cocoon. “You can’t make a heavy animatronic crawl up the wall,” said Mahan. “It’s impossible. Those are lessons learned from Predator. You can’t have a preposterously heavy thing climb upside down or down a wall with dexterity. So, for certain shots, we had to have a nimble guy on wires in a suit that matched the animatronic as much as possible.” Unlike the animatronic, the skin also employed foam latex. “The sub-base is foam rubber, so it has a lot of detail to it,” Mahan said, “but it’s got the ability to compress and move. And then it had sections over it that were made of the same material as the animatronic, so it had a matching consistency of the chest and the arms and the head. When you intercut the two together, they feel like the same creature.”

In truth, the suits’ legs and arms did not proportionally match the animatronic, but the plan was to shoot them from certain angles only. Mahan said: “if you frame away from the legs and from the waist up, maybe the arms are a little shorter, but the chest is the same size, the head is the same size, and the illusion is pretty complete. And even though he’s not eight feet tall, you can block him up on an apple box, and he’s suddenly eight feet tall, and you can make it work.”

An insert cable-controlled arm was built specifically for the cocoon emergence scene, able to unfurl its fingers from an initially folded position. “It’s like a butterfly coming out of a cocoon,” Mahan related, “where it doesn’t really have joints or bones, but it’s something interesting to look at, and it helps tell the story of how it is emerging or coming alive.”

Hero animatronic heads and “attack” heads were devised, with a gimbal system to make them appear more locked onto targets. The attack heads could evert the inner jaw with more force, necessary to punch through the human gore puppets. Both versions could also spew vapour and saliva with an on-off switch radio control. “We used air blowers to push the fluid all over the place so it’s going sideways and off to the side, it’s not just floating down,” said Mahan. “We had channels built through the xenomorph’s jaw systems that were plumbed so you could have tubes running through the head to a radio-controlled pump that would deliver fluid on and off as you wish. Two consistencies of fluid, and then high pressure blowers underneath, and there was also smoke coming out of the mouth.”

Finally, Legacy built six blow-up puppets for when the creatures are shot — fitted with foam latex organs and squibs of coloured methocel blood. These were used in the zero gravity sequence, combined and intercut with digital effects. An inert dummy of the dead Scorched Alien was also devised.

For more complex actions performed by the Aliens, digital counterparts were needed. These included limbs and tails to augment the practical versions, as well as fully digital characters. “The Legacy puppets are beautiful up close,” said Sepulveda-Fauser. “They hold up really well. But as soon as we have to incorporate specific body movements, we have to jump in with visual effects. When the Xenomorph is in motion, we can’t get a practical creature of that size to perform some of the movements required for an action sequence. In the elevator shaft sequence, for example, when he’s getting shot, or when he catches Rain, or he’s coming toward her, those scenes are a blend of our wide and medium close-ups with practical effects. We had to match the Xenomorph model perfectly so we could have closeups cut between practical and CG.”

The CG models started from digital scans of the animatronic, and the following assets were then shared across visual effects teams to maintain consistency — with the workload shared between ILM (under Sepulveda-Fauser) and WetaFX (under Daniel Macarin). Animation in Maya and Houdini was keyframe-based for the most part, with certain shots referencing performances by Newlin donning a motion capture suit.

Alvarez wanted reference from big felines, such as leopards and jaguars, but with a further sense of intent. “Their body does all these contortions,” said Barba, “but the head stays perfectly locked on its target, almost like its head is on a gimbal. And that’s how you partially know that thing means business.”

Sepulveda-Fauser commented further: “[Alvarez] didn’t want over-exaggerated motion on the creature. His concern was that as soon as it moves too much or too fast, we take the audience out of the movie, we start feeling that CG on the screen. He wanted creepier movements. That’s why there’s the slow crawling on the walls. The slower movements make it feel creepier, strange. The creature is doing something impossible — it’s crawling on a wall — yet we had to make it feel possible, ominous, and weird.”

The need for quick cuts was also emphasized upon, as stated by Barba: “when you think about Alien, Ridley used a guy in a suit for his Xenomorph. Those shots are so quick. Some are half a second, but it scares the bejesus out of you because your mind connects the dots. Fede felt strongly about keeping our shots quick so that the audience doesn’t see a guy in a suit or an animatronic or a CG version.”

One particularly complex sequence in the early third act of the film revolves around the Aliens being shot in zero gravity. The challenges for the ILM animators included animating the now weightless creatures, as well as the fluid simulations for the acid blood. “In the beginning, when we were first understanding the effect, it was a lot more subdued,” recalled Sepulveda-Fauser. “It was going to be some Alien blood in zero-g. But it’s a big action sequence and Rain’s had this big fight. There was a lot going on. The acid effect needed to have more character and quickly developed into, ‘no, the acid is an actor in this scene.’ This is a very, very scary moment. It’s got to be something else, it needs to be frightening, turbulent, it’s got to be an immediate danger that they can’t pass. And it needs to perform with intensity and visual impact.”

Despite the quasi-fantastical concept, the audience still had to believe what is happening before their eyes. Sepulveda-Fauser continues: “it took a lot of development and experimentation to get the recipe for realism so that it didn’t feel magical as in a Harry Potter movie. It was easy to go into a fantasy world really quick with this effect. We finally came to a setup that I believe was successful, so that it sold the idea that this was possible as kind of a funnel of real acid happening within the set.”

Much of the Alien action — including part of the zero gravity sequence — takes place in the hive, which was built as a 50-meter long, 8 meter high arched set. Based on concept art by Dane Hallett and Nick Stath — which referenced production photos from Aliens, as well as Giger’s art — construction was undertaken by the crew at Artoid Studio, with supervision from production designer Naaman Marshall and Monica Alberte.

For more pictures of the Aliens, visit the Monster Gallery.

Previous: Alien: Covenant

Next: Alien: Romulus, the Offspring