Content Warning: the article includes discussion and explicit pictures of Alien hybrid genitalia, which may be problematic for readers of a certain sensibility.

“You are a beautiful, beautiful butterfly.”

As an unexpected side effect of the cloning process, the Alien Queen stops producing eggs and develops a womb-like sac, out of which an abomination, an amalgam of human and Alien DNA, is born. The Newborn is the culmination of the fair of the grotesque presented in Alien: Resurrection — a direct mirror of Ripley 8’s tainted humanity.

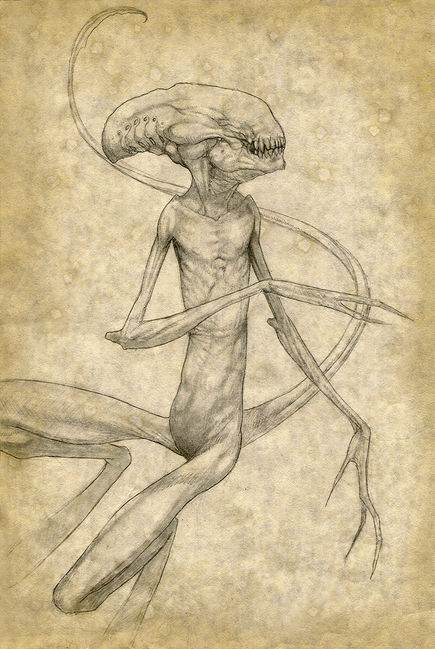

In the script written by Joss Whedon, the Newborn was somewhat vampiric in nature. It was a large, pale monster with spider-like legs and bulging veins along the sides of its elongated head, as well as pincers to hold victims still as the Newborn drains them of their blood. It is also explicitly male and attracted to Ripley 8. Jeunet did not necessarily want to adhere completely to the scripted ideas, driving the Newborn in a more psychosexual direction. He said: “we needed someone new, someone more touching — and he’s very cruel, very bad, he kills the mother. So it’s a mix of something sweet and something very tough, and this is one of the themes of this film. It’s about incest, because Ripley is the mother and she makes a kind of love with the son. It’s disturbing.”

Where Ripley 8 was a human tainted by Alien genome, the Newborn would be the opposite. “The idea of the newborn was mimicking,” said Tom Woodruff Jr.. “Much like Sigourney was a human clone whose DNA had been scattered because of alien contamination. The Newborn was going to be an alien whose DNA had been contaminated by human DNA.” Various concept sketches depicting variations on the idea were produced by Chris Cunningham and Jordu Schell. “We do a design process, there is no one direction,” Woodruff continues, “because there’s never just one design out there that’s going to work. So what we try to do is cast a very wide net and go off in all kinds of directions with loose sketches and look at different things. It’s a very organic process, one thing grows into another.”

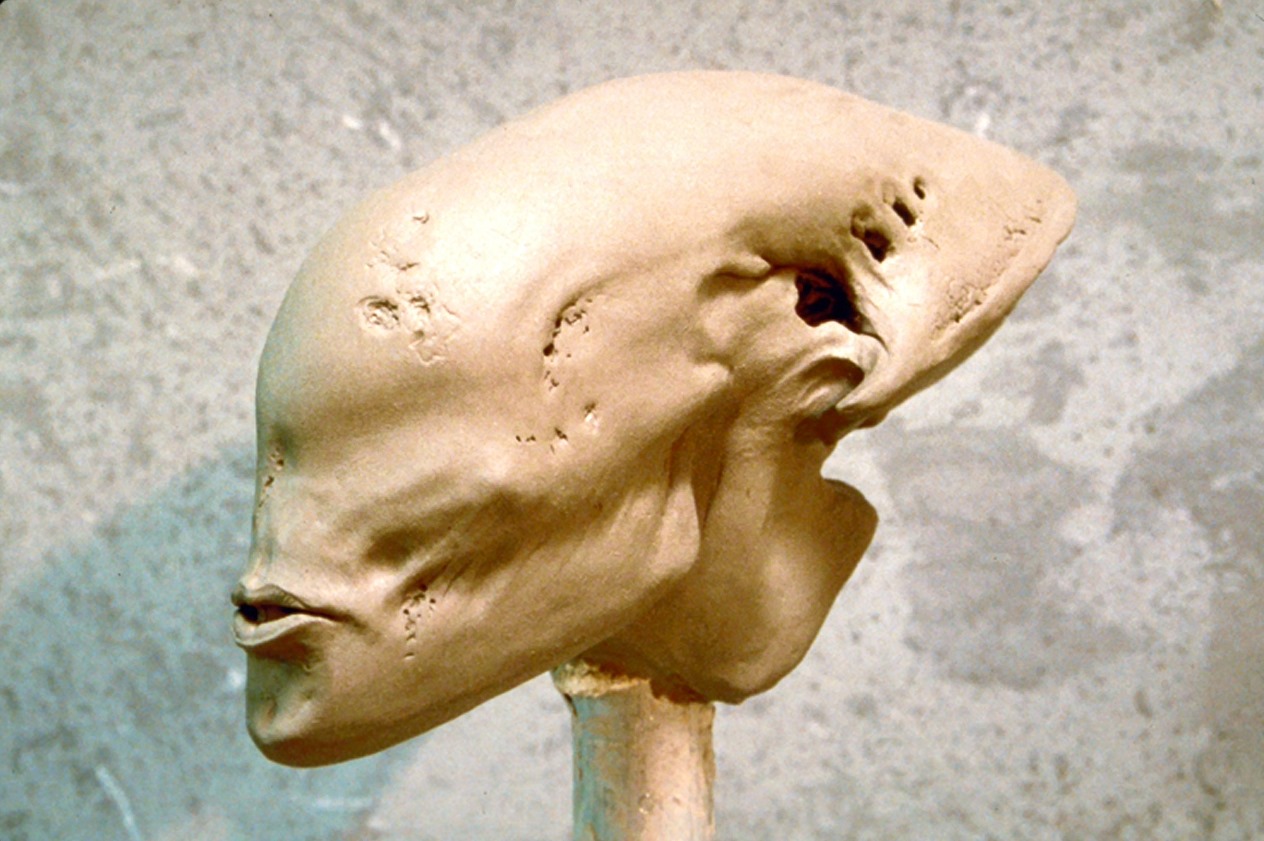

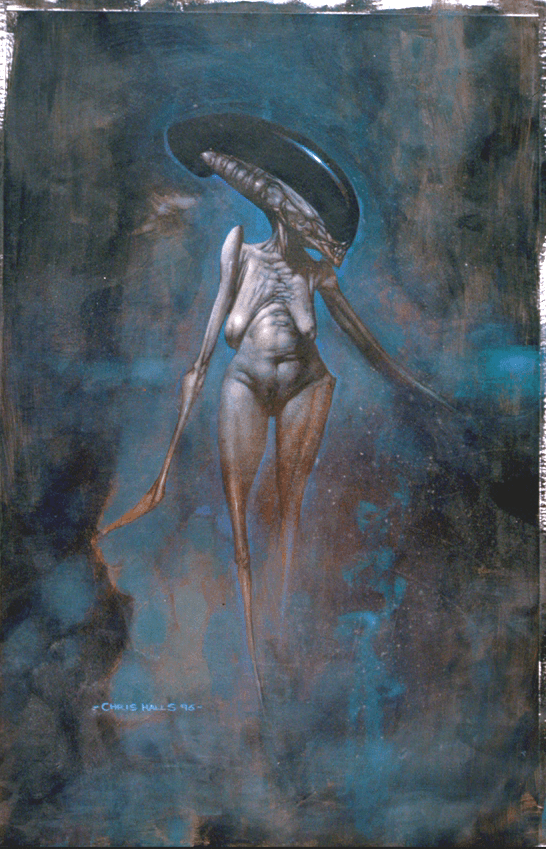

An idea that was initially proposed was that the Newborn should explicitly resemble Ripley in its facial connotations, something that the ADI crew eventually opposed against — for multiple reasons. The discrepancy between the grotesque monster body and Sigourney Weaver’s face seemed too jarring conceptually. Alec Gillis said: “we were never big believers in incorporating such a beautiful woman’s face as Sigourney’s into a monster’s face. The only time it has been successfully done has been in H.R. Giger’s paintings, where it has a creepy kind of beautiful quality. The problem with that is trying to ground it.” Another strong opposition was that a female humanoid alien, designed by H.R. Giger himself, had appeared just one year prior in the film Species. Yet still, somewhat feminine designs were explored in Jordu Schell’s maquettes.

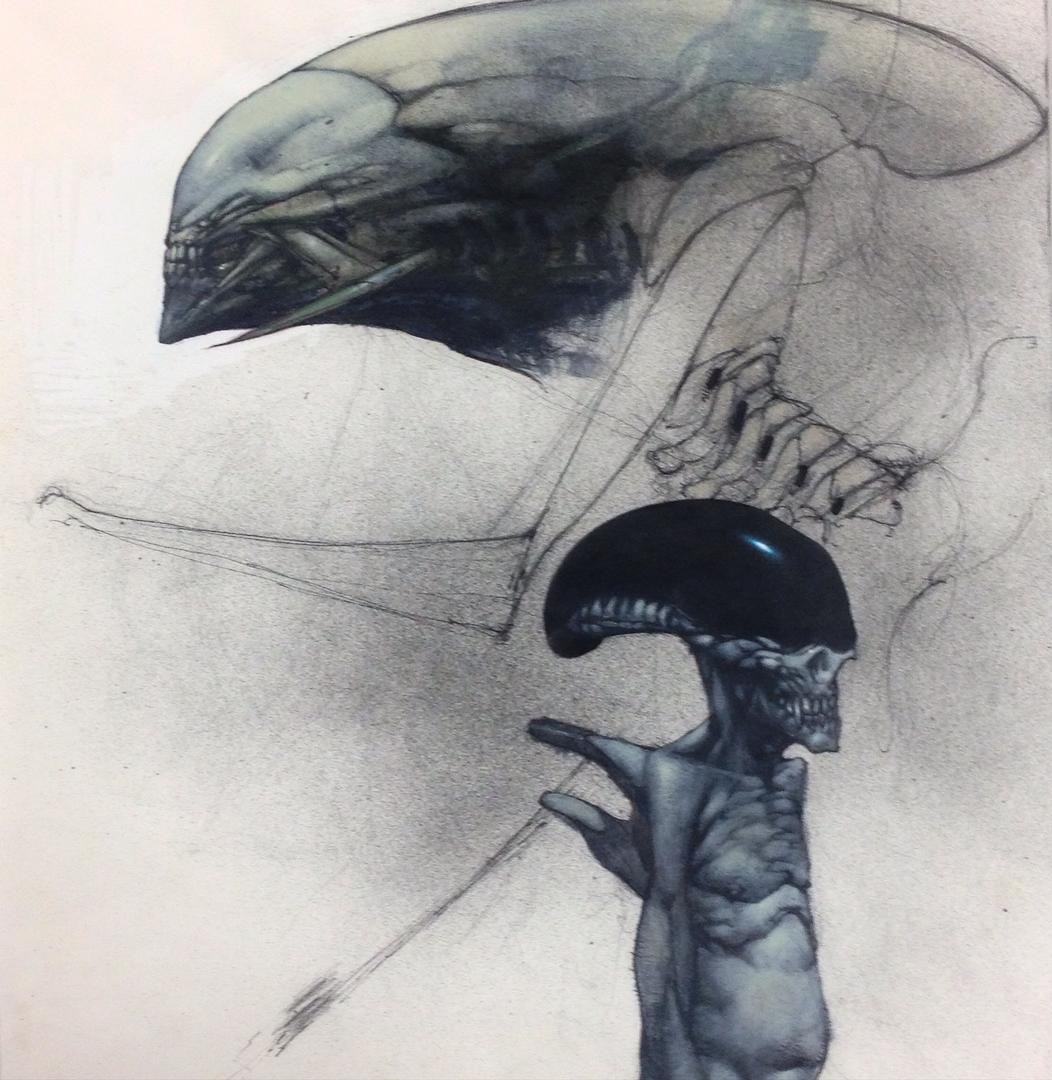

In one concept painting, Cunningham painted the Newborn in an attempt to visually convey the description from the script — which included head mandibles. On the same sheet of paper, he also sketched a caricatural humanoid design, done “in jest,” according to Gillis. In an unexpected turn of events, Jeunet responded positively to the latter, which became the basis of further elaboration — the grotesque mockery of an infant.

Woodruff recalled: “Chris did some beautiful sketches. We knew we wanted it to be a giant-sized alien and to have two arms and two legs and the long alien head and the weird body, but we decided to make it look like it was already rotting and petrified, as if it had been a dead thing that had been born and started to decompose. Chris had done a sketch that was a very human figure with this kind of sunken chest and a pot belly with an Alien head on it. I thought it was very funny. I said, ‘this looks like some old actor wearing an Alien head,’ and Jean-Pierre saw it and he said ‘I love this, this is the Newborn.'”

Further concepts by Cunningham maintained the obsidian black dome of the first sketch, as ADI wanted to preserve the signature eyeless menace of the Alien. After reviewing concepts and maquettes, Jeunet differed, affirming that he wanted eyes on the new creature. Despite agreeing with the concern about Sigourney Weaver’s connotations embedded in the Newborn’s face, the director still wanted to try eyes that looked like the actress’. “That became the biggest design conversation we had,” Woodruff recalled. “Jean-Pierre really wanted to have eyes in the Alien and we said, ‘the Alien has never had eyes and the audience has come to know it that way and come to appreciate it that way,’ and he said ‘yes, but this is different because it’s been contaminated by Ripley’s DNA, so not only should it have eyes, it should have Ripley’s eyes’. Sigourney’s got these beautiful brown eyes, and you put those eyes in this skull like face, it’s still not going to be Ripley. I was worried about it looking like a total different creature. Ultimately, we had to go in the direction the director wanted or you could say we were not successful in the derailing his wanting to see eyes.”

While the spindly proportions remained, the black dome was removed and a skeletal face was added. Gillis said: “we took a different track in humanizing the creature. We moved away from the standard biomechanical look and thought in terms of a very strong sort of classical death imagery, a skull-like face, and tried to lay it in textures that would make it look part human and part Alien.”

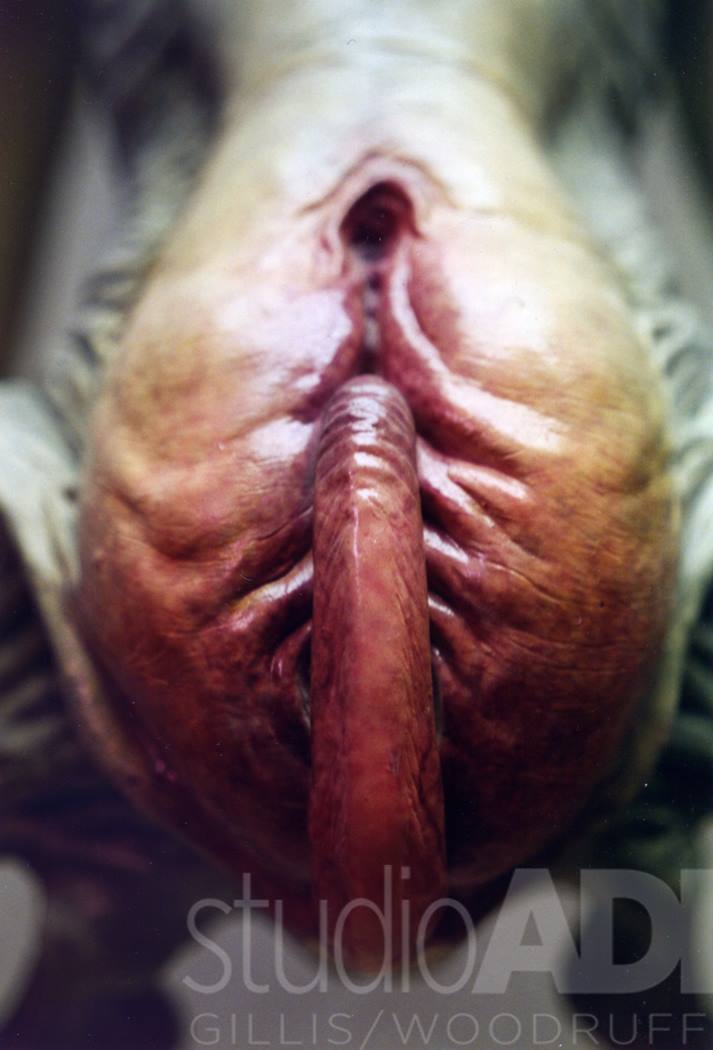

One somewhat controversial element of the Newborn design was its genitalia, something that both Jeunet and Weaver pushed toward. Gillis recalled: “Jean Pierre used to joke that, since he was French, he had to have something sexy in the movie. Sigourney is a daring actress and she and Jean-Pierre wanted to disturb the Fox executives. Sigourney, in particular, was in favor of going further with the sexual attraction between the Newborn and Ripley, to the point where the creature would have articulated genitalia.” The organs were designed to incorporate both male and female anatomy, somewhat blurring the line between sexes. Gillis added: “we wanted to be a little vague about what the sex of the creature is.”

The main design ideas converged in a final design maquette, sculpted and painted by Schell. It was faithfully reproduced in a full-scale sculpture by Jeff Buccacio, Steve Koch, and Steve Wang, with the head sculpted by Wang. The creature stood well over eight feet tall. Due to its spindly proportions, it was decided to build it as a full-size animatronic. It would be state-of-the-art and very complex, and yet had to be devised in a very short time frame. The same crew that had built the Warrior Bug animatronics for Starship Troopers was assigned to the task.

Hydraulics were employed for the main armature, which was supported by a boom arm; the very thin frame allowed little space for mechanisms inside. It could perform a full range of motion above the waist, with rod-puppeteered legs. The supporting boom was tethered to a Chapman camera dolly base, which allowed fluid motion. Almost all servo valves and electronics were mounted externally, and an internal mechanism allowed the Newborn to stretch out or compress down as needed. Servo controls in the head controlled facial articulation, with a double-jointed jaw that could perform a wide range of motion, as well as inner tubes that could pump out dry ice vapour to convey the creature’s breath. An additional mechanism in the lower abdomen area allowed the Newborn to have a humanlike erection.

Silicone skin, painted by Dan Brodzick and Mike Larrabee, covered the animatronic’s main body, with gel-filled pouches in specific areas that could jiggle realistically when the creature moved. More resistant foam latex was used for the skin of the arms, in order to sustain the weight of the hydraulic rams within. Completing the look before Jeunet and Darius Khondji’s scrutinizing cameras was an abundant dressing with methocel slime. Overall, the Newborn animatronic required five puppeteers for the face, five for the body, as well as support personnel for the motion control set-up it was connected to — which enabled recording and replay of movements. The supports would be erased in post-production by Duboi, wherever needed. A digital eye blink was also added to one close-up shot of the creature’s face, likely as a post-facto decision.

The main animatronic was supported by insert puppets. An insert head was built with an extensible tongue, two feet in length, designed by David Penikas and built by Steve Stewart. It was mounted on a cable-operated track that extended out of the back of the head, hidden by shot framing. Insert cable-operated arms were also built for a more detailed and controlled articulation of the spindly fingers, and a series of puppet combinations for the death sequence (described later) were devised. A quarter-scale rod puppet was also devised as a backup, but never actually used as the full-size animatronic performed all the intended shots without requiring intercuts or replacements.

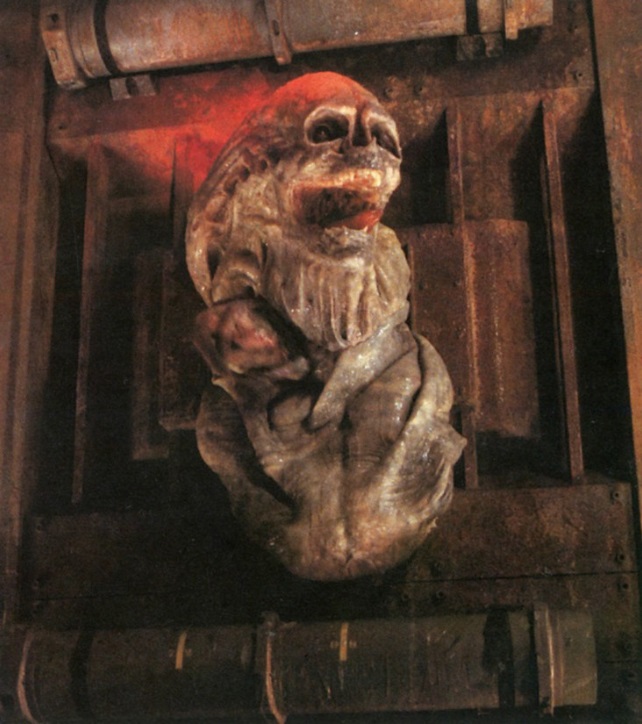

In the third act of the film, Ripley 8 is pulled down the Viper Pit and brought to the Alien nest by one of the Warriors. It is there that she witnesses the birth of the Newborn. This extremely complex sequence required over 30 puppeteers operating the Alien Queen and the Newborn from below an elevated nest set. The Newborn emerges from a foam latex placental sac that was manually operated from within to undulate and then split apart. Additional membranes made in wet pantyhose cloth, as well as thinly cast latex, were pulled down and apart as the creature’s head is revealed.

The Newborn violently rejects its mother by tearing her head off in a single claw swipe. Turning around, it recognizes Ripley 8 as a potential partner, and then devours Gediman’s brains. For this sequence, the main animatronic was intercut with the insert head. The creature is next seen aboard the Betty, and it is there that it “makes love” to Ripley 8. Takes of the creature’s tongue slathering the actress in saliva were considered but left in the cutting room floor. “It was a little bit scary, because it could have knocked Sigourney out if something happened and it head-butted her,” Gillis recalled.

This sequence would have also seen the Newborn’s genitalia in action. It was at this point that this particular feature was brought into (further) question. Gillis related: “there was also an articulated erection that we built. It sort of disengaged from the vaginal canal and came out. I think [Fox executive] Tom Rothman was the one who said, ‘we’re not having a fucking boner in an Alien movie!’ And, later on, Jean-Pierre confessed: ‘even for me, it was too much.’ But he went for it. He stayed true to the themes and was as garish as Paul Verhoeven would have been.”

Ultimately, it was decided that the genitals needed to be removed. Gillis said: “ultimately you don’t see the genitals as much — they shot around them. Because of the Newborn’s height, there was a lot of shooting over its shoulders, and in some cases they had to digitally remove the genitals. I’m not sure that has ever been done before – digital genital removal.” The “digital castration” was carried out by Duboi.

While the scripted ending featured Ripley 8 fighting the Newborn in a series of different locations (which changed through drafts), Jeunet did not find such ideas to be compelling, and ultimately decided to omit the grandiose set piece in favour of something he found more impactful. Watching special effects tests for general Perez’s death — which involved the character being sucked out of the spaceship through a small hole in the hull — the director decided to give such death sequence to the Newborn instead, making it symbolic of an abortion.

Where the original scene caused concern for ratings — due to its extremely grisly nature — it could now be even more horrific, since the victim was not human. This was also helped by the yellowish colour of the Newborn’s blood, as opposed to human red. Different stages of the Newborn being sucked out were devised, each aligned with a video switcher that could compare set-ups with previous takes.

Initially, when the Newborn is just stuck to the window, the main animatronic was used. For subsequent shots, a ‘death’ puppet was devised — a set of pullable skin and limbs combined with the insert head. The skin and limbs could writhe, dislocate and collapse backwards.

The third stage was a ‘stomach split’ puppet, whose abdomen area was prescored. As the skin was pulled from behind, it split apart, everting a plethora of silicone-cast viscera, including intestines and internal organs, which were pushed out and then yanked back with a cable.

Next, the ‘flesh donut’ puppet was employed — the disembodied head surrounded by amassed skin, which could be pulled to the point of peeling out of the skull. Finally, a breakaway skull was ruptured and pulled away, then composited — by Duboi — into a seamless flow with previous puppet.

The gore puppets were intercut with shots outside the spaceship, showing everted chunks of Newborn flesh and bones. Those were achieved by filming elements of lumpy fluids injected into a water tank, with later digital enhancement by Duboi.

“For me, playing opposite the Newborn was like playing opposite Lon Chaney Sr.,” said Sigourney Weaver. “This creature could do everything. It was immensely moving and all of my interaction with it came out of improvisation, not from the script.”

For more pictures of the Newborn, visit the Monster Gallery.

Previous: Alien: Resurrection

Next: Alien Vs. Predator

Welcome back! This is fascinating reading – I’d long forgotten this film but will have to give it another watch with all this in mind now.

Thank you Ryan!

I feel like one can enjoy the movie more as part of Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s filmography. It is very comic book-like, drawing inspiration from Le Metal Hurlant and the likes

dude, i had no clue that the relationship between the Newborn and Ripley was supposed to be incestual! i thought it was a “Momma and baby” kind of relationship.

It seems the sexual aspect was dialled down a notch in the theatrical release, even enforcing the parental aspect through dialogue