“Nature is a strange thing, I learned. You learn that very clearly when you work in a museum. You realize how nature uses the art of camouflage.”

-Donald A. Wollheim, Mimic

The original Mimic short story, penned by Donald A. Wollheim and first published in 1942, was widely different in both plot and tone to Guillermo Del Toro’s film adaptation. The titular Mimic of the story is a mysterious ‘man in a black coat’ that sneaks around a neighbourhood. When this figure is found dead in its apartment, it is revealed to be a gigantic insect, evolved to camouflage itself among humans — mimicking their appearance.

“At first we saw a man, dressed in a somber, featureless black suit. he had a coat and skin-tight pants. His hair was short and curly brown. it stood straight up in its inch-long length. His eyes were open and staring. I noticed first that he had no eyebrows, only a curious dark line in the flesh over each eye. It was then that I realized that he had no nose. But no one had ever noticed that before. His skin was oddly mottled. Where the nose should have been there were dark shadowings that made the appearance of a nose if you only glanced at him. Like the work of a skillful artist in a painting.

His mouth was as it should be, and slightly open — but he had no teeth. His head was perched upon a thin neck. The suit was — not a suit. It was part of him. It was his body. What we thought was a coat was a huge black wing sheath like a beetle has. He had a thorax like an insect, only the wing sheath covered it and you couldn’t notice it when he wore the cloak. The body bulged out below, tapering off into the two long, thin hind legs. His arms came out from under the top of the ‘coat’. He had a tiny secondary pair of arms folded tightly across his chest. […]

The lower thorax — the ‘abdomen’ — was very long and insectlike. It was crumpled up now like the wreck of an airplane fuselage. I recalled the appearance of a female wasp that had just laid eggs — her thorax had that empty appearance.”

-Donald A. Wollheim, Mimic

The creature had made a small apartment into its nest. Dozens of newborn insects – the Mimic’s own offspring – fly out of a window. They “were two or three inches long and they flew on wide gauzy beetle wings. They looked like little men, strangely terrifying as they flew — clad in their black suits, with expressionless faces and their dots of watery blue eyes. And they flew out on transparent wings that came from under their black beetle coats.”

Just after the creatures vanish, the narrator notices something else: among the countless chimneys on top of the other buildings, one is revealed to be a chrysalis of yet another species: “I saw it suddenly vibrate, oddly. And its red brick surface seemed to peel away, and the black pipe openings turned suddenly white. I saw two big eyes staring up into the sky. A great, flat-winged thing detached itself silently from the surface of the real chimney and darted hungrily after the cloud of flying things. I watched until all had lost themselves in the sky.”

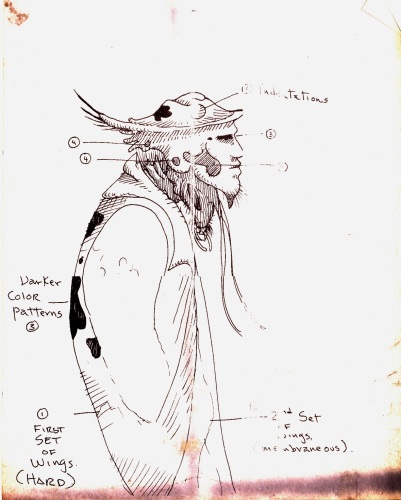

“The idea on the pages was that at night in an alley, you can see a guy in an overcoat and not notice that he’s not human,” Guillermo del Toro said. “Basically, there’s always someone in a neighborhood who people don’t pay that much attention to, and in this instance, that this someone is a something.” Originally, the cinematic adaptation of Mimic was conceived as part of an anthology of four short, half-hour long films (each directed by a different director), titled Lightyears. For the project, TyRuben Ellingson was brought onboard to elaborate designs for the Mimics

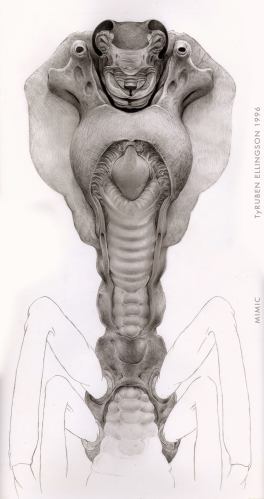

The process began with a single concept drawing by del Toro himself. The creature evolved human-like features both to live unnoticed amongst humans and to prey on them. “From the very beginning, it was decided that the Mimic creature’s ability to pass itself off as a human would be exclusively a function of its biology,” Ellingson said. “A cleverly placed appendage could, in the shadows of evening, appear as a face, or a turned wing resemble a homeless man’s tattered overcoat.”

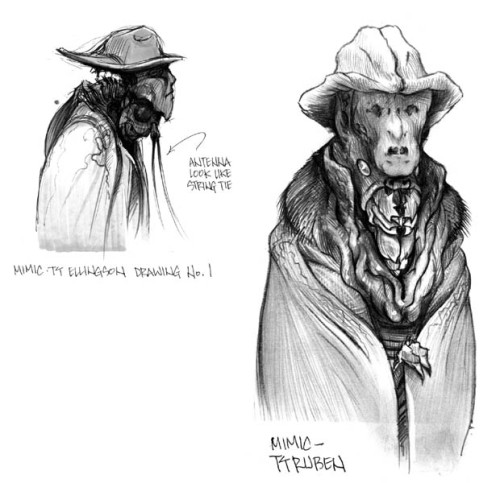

“In this sketch,” Ellingson commented, “you can make out the early ‘head with brimmed hat’ idea that we moved away from shortly after I got involved. If I remember correctly, it had to do with who actually wore brimmed hats, and what kind of statement that might make to the viewer. As the Mimic was to be perceived as a derelict of sorts — a homeless person — the idea of a small tight fitting hat, or hood, quickly got traction after I shared my first few drawings with GDT.”

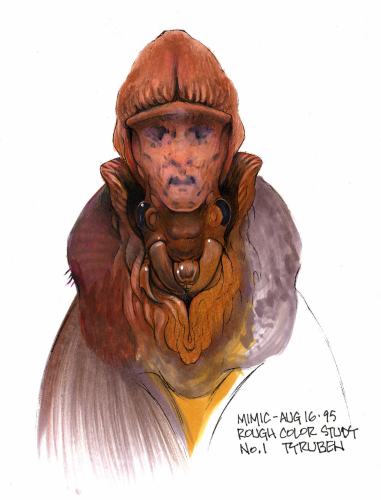

On this latter concept, Ellingson stated that “this hood and face are actually a shell-like structure and soft membrane that the insect could ‘fold up’ or ‘puff up’ into the proper shape atop its head. The insect’s actual eyes and mandibles would then tuck into a fleshy pocket under the ‘counterfeit faces’ and ‘false chin’. You can see the insect’s black eyes on either side of the ‘neck’, just inside a faux collar.”

The original Mimic design was translated into a reference maquette. All design elements were maintained: the shell-like structure became a crown protruding from the top of the Mimic’s actual head. Spots of varying tones (unseen in the mostly unpainted maquette) created the illusion of facial features — a trait recalling the description in the short story. The large upper head was covered by a membrane resembling the hood of a jacket.

Shortly after the creation of the maquette, discussions began about transforming Mimic into a full-length feature film. In a few weeks, del Toro pitched an idea to expand on the basic concept and began to write the new script. The original plot of the novella was abandoned, in favor of a wider new story. Del Toro wanted to expand on a specific theme: the “desecration of whatever we hold holy, and whatever gives us our place in the evolutionary chain and spiritual chain”.

Del Toro was initially against explaining what the Mimics are, but studio interference forced him to develop a precise backstory. The new Mimics would eventually become the result of a quickened evolution process starting from bio-engineered insects — the Judas Breed — supposed to eradicate disease-spreading cockroaches. Del Toro originally envisioned the Mimics as an advanced species of bark beetles; executive producer Michael Phillips insisted on making them cockroaches, or cockroach-like. Del Toro said: “things started deteriorating early on. In the original draft, Matthew Robbins and I did we had the creatures being bark beetles — white oak bark beetles from New York– that nested in Central Park and they were carriers of a bacteria and they needed to be controlled. I will never forget the day where Michael Phillips, having removed his loafers in a meeting, proceeded to say, ‘well, if it’s New York, what about cockroaches?’ I felt the world had exploded in a wave of horror for me and right then and there I said, ‘listen guys, we shouldn’t do that, because from now on we’re going to be the giant cockroach movie and there is no way you can go past that absolutely Z-movie conceit. We may be able to show we are a smart movie, but the cockroach, in and of itself, is such a demeaning, fundamentally Z-movie concept to create a movie around we’re never going to outlive that.’ Essentially, I lost that argument because somebody at the table was very enthusiastic, New York, cockroaches, that’s a perfect marriage, blah, blah, blah.”

“When Guillermo and Matthew [Robbins] set to work on the new full-length script,” Ellingson said, “I went back to the drawing board as well. The new story was going to have a different spin on a number of the original story elements from the short — different set pieces, and a great amount of new material — as such, our creature needed to evolve as well.”

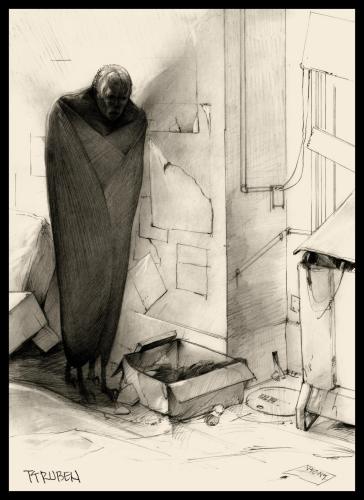

“As we moved forward with the design development curve, the brimmed hat idea was abandoned largely because so few people wear such hats anymore,” Ellingson said, “and concern arose that this gave the Mimic creature a bit too much of a whimsical vibe.” Ellingson produced a new drawing with a simpler humanoid configuration, and the wings of the insect folding over its body, mimicking a long coat. This concept laid the foundation of the final Mimic design, with all subsequent developments of the creature following its template.

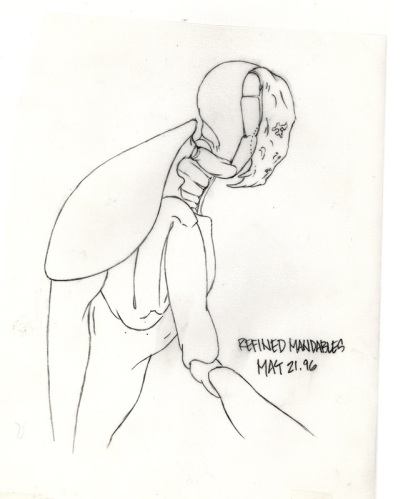

The illustration was purely conceptual, however, and the creative team still had to elaborate on how the Mimic would take on the appearance of a human face. After thorough research on insect anatomy, Ellingson settled on two “faux face-mandibles” or “face-claws”. He explained: “the sketch of the Mimic in the alleyway […], though simple and monochromatic, really seemed to hit a proper chord for the picture — yet the question remained, how exactly would a large insect take on this shape? I explored a number of ideas as to how this kind of ‘biological disguise’ could be accomplished. After some sketching and researching, the idea of a set of large mandibles with face-like textures on the outer side of them was devised. These special ‘faux face mandibles’ would be positioned up near the head at ‘the shoulders’ and allow the creature to hold these special appendages up over its real insect head to create the illusion of a human head and face; an idea that we retained in various forms, until the completion of the final design.”

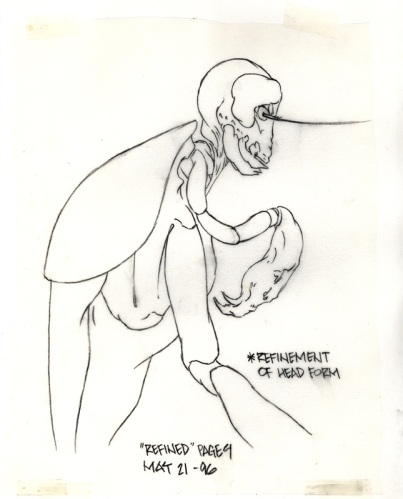

Following the idea, Ellingson produced a new concept illustration. In reviewing it, Del Toro and Ellingson decided that the ‘faux face mandibles’ would actually cover the Mimic’s head rather than just being held in pose in front of it — an idea they called the “peek-a-boo mandibles”. Ellingson related: “Guillermo and I came around to the idea that it would be much scarier if the faux face mandibles could — rather than just being held up in the air — actually ‘cover up’ the insect’s face. Once accomplished, when the creature was set to attack, this reveal of its biting jaws would be fast and unexpected — the movement similar to that of what a parent does with a child when playing peek-a-boo.”

“From the front of the creature, the earliest versions of the peek-a-boo mandibles (when closed over the insects true head) came together in two simple halves with a straight vertical joint between them,” Ellingson said. “Later, this simple joint in the face evolved into something more jagged and organic. This simple adjustment not only allowed for the “face” on the mandibles to appear less symmetrical like a Rorschach test, it increased the frightfulness and menace when the reveal of the insect head hidden inside was executed.”

Concurrent with the design development was the need to begin work on the actual full-size Mimic animatronics required for the picture. Rick Lazzarini’s Character Shop was hired for the task, in light of the realism of their work on Outbreak, the elephants for Operation Dumbo Drop, and the frogs featured in the Budweiser commercials. “He [del Toro] said that a few of our puppets were the most realistic things he’d seen,” said Lazzarini, “and he thought that that kind of approach works well, whether you’re doing something that’s scary or cute or what have you. It’s an attention to detail that works across the board.”

A team of sculptors, including Lee Joyner, started blocking the full-size Mimic body even as the design process was still underway. During the early phases of sculpting, Ellingson returned to the early idea of a ‘springing neck’ for the Mimics. “Guillermo had always talked about wanting the creatures’ real head to be able to spring forward away from the body when attacking its prey,” he said.

As the sculpture of the full-size creature was underway, Ellingson provided the sculptors with reference drawings for shapes and textures of the Mimic for each one of its body parts. Real insects used as reference included mantises and African leaf-cutting ants, as well as cockroaches.

During this sculpting stage, Del Toro decided to further elaborate the texture of the Mimic’s chest, instead of leaving it as a simple, hard-shelled surface as it had been previously established. Ellingson explained: “in early rounds of the Mimic design development, the chest of the creature was kind of a smooth rounded shell with a fleshy pocket in front. Later in the process, when we moved on to making maquettes, this direction was drawn into question. Del Toro grew concerned that this area of the Mimic’s body, being very prominent on screen, was not interesting enough, and not photographed in a creepy or scary way. In response to this, I proposed creating a kind of ‘meaty gill’ pathway into the creature which transitioned down into a more pupa-like organic abdomen.”

This choice reflected a crucial story point related to the Mimics’ size — explained by the filmmakers as a benefit of evolving lungs.

Ellingson further elaborated on the idea: “reflecting on early sculpting of the creature’s chest, an area of the body which had always been thought of as being a hard shell, Guillermo raised a concern about it being too simple in form. As is often the case when taking a concept from flat artwork to three dimensions, one finds that adjustments are required. After a brainstorming meeting in which we dramatically lit the clay sculpture and viewed it through a camera, we concluded there was room for improvement. After a series of sketches, I developed this drawing in which I proposed creating a kind of ‘meaty gill’ pathway into the creature which transitioned down into a more pupa-like organic abdomen. This solution pleased the director and alleviated his simplicity concerns. Though the concept evolved as the sculpting proceeded, this drawing became the touchstone for the change in direction.”

Another key design element was inspired by mantises: a switchblade-like tarsus that could be folded into the arm — concealed by a human hand-like protrusion of the tibia — and deployed at will to stab and cut.

At this point, Ellingson shifted away from the Mimic design — only providing colour scheme patterns for the Mimics — and moved on to other tasks in the production. Rob Bottin was brought in as a creative consultant to refine the Mimic design. “Rob gave it a more menacing profile and added a lot of sharpness,” Lazzarini commented. “While insects are nasty and creepy, if you look at photo blow-ups, many of the appendages are kind of knobby and soft, and we had originally gone a little more like that. What Rob brought to the party was ‘hey, let’s make these things more menacing – who cares if that’s what they look like in real life? Let’s take those feelers and mandibles on the face and make them dagger-sharp’.”

The Mimic design underwent sculptural modifications due to studio interference. Misunderstandings on executives’ part were very common, oftentimes reaching the absurd. In one instance, an executive forgot that the Mimics were insects, and demanded that they look less like such. This was recalled by Del Toro in the commentary for the Blu-ray release of the film: “the Mimics used to have antennas, but the feedback we got from the studio was a raging phone call where they said, ‘they look like bugs. The Mimics look like bugs.’ I said, ‘but of course, we’ve been developing the creatures for a year-and-a-half, you’ve seen the designs, you’ve seen the maquettes, you’ve seen the clay molds, you’ve seen everything and they are bugs.’ ‘Well, can you make them more like aliens?’ I said, ‘I don’t want to make them more like aliens. At this stage we already have functioning puppets with radio-controlled servos, animatronics. What do you mean redesign them?’ And somebody said a really great line, they said, ‘can you make their teeth bigger?’ I said, ‘They don’t have teeth.’ ‘Well, show more of their gums.’ I said, ‘they don’t have gums! They have a multi-part, mouth system!’ ‘Well can you give them crazy hair?’ ‘They don’t have hair, they are insects.’”

This counterproductive back-and-forth lasted two months until the final iteration of the creature — dubbed the ‘Long John’ design — was obtained. Among the losses of the design were the antennas, replaced by “antenna-nubs” that vaguely resembled bloated human eyes.

Despite the long and difficult process, the director was satisfied with the final creatures. “Beautiful, fast, like a stealth bomber, really aerodynamic, sharp, yet when you see it, you see an insect”, said del Toro, “an insect that has changed, but nevertheless an insect. We used different genetic codes from different species. When I spoke with them about the colors and textures, we always said ‘look at the books – be absolutely faithful to nature. Let’s make these creatures real’. […] [It is] a monster that is not a monster, what I call the National Geographic approach – the creature has to be beautiful and fascinating because of this, not extra spikes and huge teeth and glowing eyes and hairy bottoms.”

The Mimics are sexually dimorphic, reflecting the advanced sociality of their species. The female is winged, and its colour scheme was based on a cockroach. The male, while based on the female sculpture, applied some notable modifications — such as the lack of wings and the pale colour scheme. The male also lacks the ‘faux face mandibles’.

Several scenes depicting the Mimics’ society and intraspecific interactions were cut due to creative disagreements from the studio. Del Toro explained: “originally, Matthew Robbins and I came up with the idea of having a huge nest, since the single male is the one that impregnates all of the females in the nest, like the termite colony where there is only one king. In order to show that Matthew came up with a disgusting image, which was to have the final chase happen after we see a cluster-fuck — literally, a cluster-fuck of insects in the wall — and you see the male coming after them with the female still attached to its penis. [We had] these twin bodies, in perfect coordination, running after them in the tunnels of the subway and I thought that was a brilliant image, but the studio thought it was repulsive, repugnant and the way they can control you very easily is budget. It was also, sadly, very expensive and so it was cut from the film.”

The “cluster-fuck” scene was also crucial for one of the main themes of the film — the question, “what if God has forsaken us and wants to replace us with something else?”. Del Toro explained: “Giancarlo [Giannini] finds Chuy and that’s where we discover the giant wall of fuck, the male fucking all the females, the female attached to his penis… it was an absolutely nightmarish moment and the character of Giancarlo sees the creatures coming for him and he uses his razor blade to cut his own throat saying, ‘God cannot see this.’ I really liked that, because I felt he could bring the religious angle to the movie. He could say, ‘what if God has abandoned us? What if he has made us not his favorite creatures anymore? What if these things are taking over?’ And all of that is lost in the movie, and those are things I truly missed.”

Mimic employed a diverse number of effects techniques, ranging from full-size puppetry to digital animation. The visual effects — which amounted to 85 digital shots in the film — were delivered by C.O.R.E., Digital Domain, and Hybride. The Character Shop covered the entirety of the practical creature effects for the film, and built Mimic puppets at various scales: those included small scale rod puppets and imposing, seven feet tall full-scale animatronic creatures. The rod puppets were largely employed in the explosive finale of the film, composited among the fireballs and digital Mimic body parts. When the male Mimic is run over by the train, the frantic sequence also employs a rod puppet, combined (or intercut) with the digital model and body parts that are ripped off of the creature as it is overwhelmed by the force of the vehicle and ultimately minced.

Only one hero male full-size animatronic was built, whereas at least five female animatronics were produced. They were painted by a team led by Tom Killeen, who “took his cues from nature, brilliantly and intelligently duplicating the patterns, colors and hues of real cockroaches,” as related by Lazzarini.

All of the full-size puppets could perform a wide range of motion, with full articulation of their limbs. Their heads could move their mandibles and other parts: “as in a real insect of this type,” Lazzarini said, “the mouth parts all move together: the labrum in and out, the minor and major mandibles scissoring, clamping, and bringing the food to the mouth, an opening and closing jaw, a tubular tongue that oscillates in and out, and four waving palpi to help scrape up the loose bits. We took artistic license with the labrum and palpi, making them end far more pointed and ‘fangy’ than a real insects’ do.”

Lazzarini added: “mechanical co-supervisors Scott Oshita, Gary Martinez, and Dave Kindlon did an excellent job or wrangling the designs and the workers and subcontractors to build them. Kudos [sic] to Sam de la Torre for his ‘heading up’ the assembly of seven different, very complex radio-controlled heads. That’s three transmitters per head on the more ‘hero’ models!”

Various materials were needed in order to build and assemble the various components, as related by Lazzarini: “the head is polyester resin and fiberglass, with cast-resin mandibles. All mandible movements are radio-controlled, while the head and neck movements were cable-controlled. The neck is plasticized silicone, and given body by nylon rings. The torso, carapace, forearms, main claws, and pelvis are fiberglass and polyster resin, all other limbs and wings are vacuformed. The arms and legs are all rod operated, with the ‘switchblade’ operation of the main claws via cable control.”

Those materials were lightweight, allowing the animatronics to perform more fluid and less restrained movements. Additionally, they enhanced the creatures with an organic, semi-translucency typical of many insect species. The parts that were to be moulded in vacuform were voluntarily ‘oversculpted’, since they would lose detail resolution during the moulding process. Nylon, dental dam and silicone were also employed for the gill-like lungs and the joints, providing them with stretchability and bendability. The lungs were also puppeteered with internal bladders.

Lazzarini related: “a post came out of [the puppets’] back to enable us to puppeteer the torso at a flexible point above the pelvis, and the pelvis had a very cool spud system so that we could mount it from below, in back, or etiher side. The spud then got held in a boom [or] dolly, which enabled us to raise, lower, swing, and truck the whole insect puppet along. While not every bit needed to be controlled for every shot, we could some times get by with only four puppeteers, other time needing as many as eleven. The scene where they are outside of the switchhose window, and then turn to react to Charles Duttons’ character singing, was the most difficult and puppeteer-populated — 26! — shots we did.”

Small-scale puppets were also experimented with, with rod puppets of both male and female Mimics constructed with similar material choices as the full-size variants. Ultimately, the footage was only used as reference, with the puppets replaced by digital creatures.

A very in-depth study was put behind the motion of the Mimics. They could walk with two different configurations: on all six limbs, they use a triad locomotion; the research for the facehugger movement in Aliens helped establish the coordination of the limbs during movement. When mimicking men, however, the creatures adopt a humanoid, upright stance, standing on four of their long and thin legs. Hindrances due to size were simply resolved with creative liberty.

The rules applied practically with the animatronics were also applied to their computer-generated counterparts, crafted by C.O.R.E. Digital Pictures model makers David Asling and David Axford, based on scans of the rod puppets. The animation was performed by a team led by John Mariella and Bob Munroe. The digital Mimics were employed for scenes where neither the full-size puppets nor the small-scale ones could perform the desired movements — such as flying, running or crawling on walls. Body language for the digital creatures combined motion elements from insects, as well as horses, bulls and rhinos, combined with smoother, more humanoid traits implying higher intelligence.

“There’s a reason why an insect skitters as fast as it does and an elephant lumbers as slow as it does,” explained Lazzarini, “and that’s because of the difference in mass and weight. That’s why you don’t see huge insects [in reality], because, pretty soon, you start to develop a need for internal structure with external muscles. If you do take that leap and say, ‘we’re going to make an insect 6 feet, 7 feet tall’, it wouldn’t move as quickly as a small insect does. If you’ve seen a bull charge — or a rhino — it’s surprising how fast something of that bulk can move, so we took that into consideration. We’ve got the insects probing and walking, and other times when they’re lightning fast. We got all the natural references in a pile and said, ‘these are the rules we can go by’, and there were also times when we said ‘let’s take some artistic license with that. If it makes the scene go beyond those rules, we’re going to do it’.”

The film also shows various phases of the Mimic life cycle, which starts with a small nymph stage. Much like the adults, it also underwent many design iterations. The core concept was to combine a cockroach and a mantis with razor blade-like shapes. In the film, it is brought to life with cable-controlled animatronics intercut with digital animation.

One key sequence of the film involves the autopsy of a Mimic juvenile, dubbed “Dead Boy” by the effects team. Lazzarini explained: “originally, he was going to be bobbing about in the sewer halfway exposed and be fished out. A sewer worker was going to say “C’mere…I think it’s a kid!”, and you were gonna think it was Chuy. Hence, our calling it the ‘Dead Boy’. Of course, things changed. For the better, always, right?”

Construction of the Mimic juvenile — two copies of which were built — was completed before a general revision of what the ‘face-mask’ patterns should look like. Given that it was supposedly an immature individual, the filmmakers ultimately decided to maintain the initial design. Rick Lazzarini said of the creature: “It’s really just a juvenile version of the adult-sized Mimic creature, but with Jerusalem-Cricket-like fleshy tones to designate its youthfulness… kind of the way grubs are yellowy or fleshy. We had a couple of entomology experts come in for in-shop lectures on insect anatomy and locomotion. We borrowed liberally from cockroaches, grasshoppers, ants… sort of a best hits of insect anatomy.”

The Mimic juvenile was constructed in unplasticized silicone, cast from a silicone mold, with a polyfoam core that allowed it to float in the sewer waters. For the autopsy sequence, under directions from del Toro, the insides of the juvenile were actual organic matter (in the tradition of the Facehugger from Alien) — which included enoki mushrooms and trout entrails. This was a particularly unpleasant experience for the cast, due to the strong smell. Lazzarini related: “in the scene where sewer-boy […] says “it’s a lobster, right?”, we dabbed at the body with syrup and then put mealworms — stand-ins for maggots — in the syrup. They hated the syrup. And Mira hated the mealworms! Apparently, despite her crash course in entomological studies, she remained a bit squeamish at interacting with real bugs. So her character being at unease in that scene wasn’t all acting! For the scene where F. Murray Abraham […] dissects this juvenile Mimic, Guillermo wanted real guts. While we could have made up some fake guts, it would have cost more and taken longer. So, we went out and found the sickest mushrooms (enoki), fruits (cherimoya flesh!), fish (trout entrails), sweetbreads, brains, and other yuck. The drawback was, it stunk up the place! We were filming at my alma mater LMU, and the corridors of the science building reeked of our offal. We weren’t real popular on the set that day. But, there again, we got some good expressions from the actor because we created the proper ‘atmosphere’! And when F. Murray probes the body and tells us ‘these are perfectly formed organs…’, he’s right! They were perfectly formed trout gills!”

The young Del Toro came out of Mimic in trauma due to studio pressure and interference. Despite that, he maintains that it was a learning experience. “I was condemned to do the best giant cockroach movie ever made,” the director said. “That was the biggest achievement I could aspire to on Mimic, but damn it I tried to do it and so did everyone on my team.”

Ellingson remembers the experience somewhat more fondly: “all in all, Mimic was a fantastic chapter in my life and established a quality relationship with a director who I greatly admire. Viva Guillermo del Toro!”

Special thanks to TyRuben Ellingson for providing invaluable insight on the Mimic design and effects! Be sure to visit His website.

For more pictures of the Mimics, visit the Monster Gallery.

To see exclusive concept art, see: Exclusive: TyRuben Ellingson’s Mimic concept art!

Reblogged this on That Dark Alley.

Edited version missed the “yuck” factor…

Nei film successivi il mimetismo dei Judas comincia ad essere esageratamente simile a quello de La Cosa.

I concept di Ellingson,con il finto cappello e la finta testa, sono affascinanti.Strepitosi,secondo me, da riportare su un modello reale.

Non che mi dispiaccia,comunque,la scelta definitiva.Anche se il maschio lo trovo un tantino anonimo.

A XXX sexual parody could use the concept of bedbugs…

thats pretty cool information.

[…] Additional Data: Wikipedia Monster Legacy […]